The emergence of new surgical technologies and the possibility of performing simultaneous, combined and hybrid interventions have significantly expanded the indications for surgical treatment of patients previously considered inoperable. “Liberalization” of indications, as a rule, implies not only the improvement of intervention techniques, but also the ability to operate on patients with concomitant diseases, including chronic kidney disease (CKD). According to epidemiological data [1, 2], 36% of people over 60 years of age have a reduced glomerular filtration rate (GFR) of varying severity, which significantly complicates the course of the postoperative period and contributes to the occurrence of complications in the urinary system. In intensive care units of a general surgical hospital, the incidence of acute kidney injury (AKI) in the postoperative period is about 6% and is associated with 50-60% mortality [3, 4]. In most cases, AKI occurs against the background of existing perioperative complications, worsens the patient’s clinical condition, sharply increases the likelihood of death and significantly increases the financial costs of treatment. In 35% of cases of complicated postoperative AKI, it is accompanied by multiple organ dysfunction syndrome, the main cause of death in intensive care unit patients [5], while mortality increases to 70% [6, 7]. The mechanism of development of AKI in the postoperative period is usually characterized by a combination of several factors - a decrease in renal perfusion against the background of circulatory failure and endogenous intoxication. With the development of severe complications accompanied by AKI, methods of temporary replacement of insufficient renal function are increasingly used [8]. Despite a significant number of publications, answers to questions about the methods, duration and criteria for starting and ending renal replacement therapy (RRT) remain controversial. There is a lack of convincing data on the impact of these factors on the survival of critically ill patients and the recovery of renal function. According to some authors, this is due primarily to the severity of multiple organ failure syndrome and the degree of intoxication, since, in addition to renal failure, the mortality rate is influenced by the number and degree of dysfunction of other organs and systems. The listed and other factors determine the heterogeneity of groups requiring RRT within the general surgical intensive care unit [9–11].

The purpose of the study is to provide a clinical assessment of cases of acute AKI in patients in a general surgical hospital who underwent routine surgery and required the use of RRT.

Material and methods

A retrospective analysis of medical records of patients in the intensive care unit (ICU) for 2012–2017 was carried out, who required RRT after planned surgical interventions with the development of AKI. The study included patients operated on for diseases of the hepatobiliary zone, gastrointestinal tract (GIT), lungs and mediastinum, blood vessels, spine, as well as patients after microsurgical and neurosurgical interventions.

Indications for starting RRT were the ineffectiveness of conservative therapy to maintain homeostasis (acidosis, electrolyte disturbances) and/or increasing hyperhydration (positive fluid balance over 12-24 hours of observation against the background of oliguria, refractory to infusion and diuretic therapy).

The choice of RRT method was determined in accordance with the goals and objectives of treatment. The hemodiafiltration procedure was carried out using high-flow dialyzers. The choice of dialyzer area, fill volume and ultrafiltration coefficient was correlated with the patient's body weight and the tasks performed. Priority was given to high-volume filters (ultrafiltration coefficient more than 50 ml/h∙mmHg) with an average filling volume of about 100 ml; such filters more effectively remove low-molecular substances and have improved parameters for removing medium-molecular substances. The choice of dialysate solution was determined based on the patient’s ionogram and the duration of the session. Preference was given to acetate-free solutions with glucose. To prevent cardiac complications, when the blood potassium level was not higher than 4.5-4.8 mmol/l, the choice was made on a solution with potassium 4 mmol/l.

Heparinization during the RRT session was carried out in doses with unfractionated heparin under the control of AST (activated coagulation time 180-220 s). If necessary and possible, the procedure was performed without an anticoagulant. The criteria for stopping RRT were normalization of water-electrolyte and acid-base status against the background of normalization of diuresis.

The severity of the condition and the prediction of mortality were assessed upon admission to the ICU and at the time of initiation of RRT using the APACHE II and SOFA scales (in patients with sepsis). GFR was estimated using the MDRD formula. AKI stage was determined using the KDIGO scale.

Localizers

The most advanced companies are moving not only the provision of services, but also production to Russia, thus forming a vertically integrated structure.

In 2005, the Russian JSC Rester and FMC signed a contract to organize the production of solutions for peritoneal dialysis. It took a couple of years for technical equipment, trial releases and paperwork, but in 2008 the pioneering Rester‑Fresenius production line was launched. FMC received the exclusive right to sell products in all regions of Russia, except for Udmurtia - the plant itself sells solutions to its native region.

Currently, FMC imports equipment and consumables for hemodialysis from Germany, but by 2015, together with its partner, it plans to open the Gamma research and production complex in Dubna, which will produce equipment for dialysis and produce artificial kidneys. Thanks to this, FMC plans to reduce costs, and in addition, to establish useful connections in government, because one of the founders of Concor is the first deputy chairman of the State Duma Committee on Science and High Technologies Vladimir Kononov.

However, FMC will no longer become, as planned, the first company to produce artificial kidneys in Russia. Here the leader of the dialysis market was bypassed by another deputy - Alexander Petrov, one of the founders of the Yekaterinburg holding company "Yunona", and now a member of the State Duma Committee on Health Protection and, concurrently, a member of the supervisory board of the NP "Ural Pharmaceutical Cluster". (a member of the Ural Pharmaceutical Cluster NP) has already launched a production line for Malachite dialysis machines. Here, in the Urals, they also produce water treatment systems for medical institutions, liquid and dry dialysis concentrates for the treatment of chronic renal failure. The plant's products are supplied through auctions to budgetary medical institutions, but private dialysis facilities are also equipped with them - in Perm, MC "Lotos" - in Chelyabinsk, Magnitogorsk and Miass.

Following the example of foreign competitors, the Ural Pharmaceutical Cluster NP is developing its own network of dialysis centers: nine centers have already been built and three more are planned to be opened. Currently, 1,008 people are receiving treatment in the Ural network; the potential capacity of the centers, when working in four shifts, can reach 1,968 patients. Competition with Western companies does not frighten the Russian network.

Petrov relies on patriotic rhetoric: “Russian companies are more flexible and successful at the local level. And the presence of foreign companies makes us stronger. FMC builds itself and buys ready-made networks all over the world. On the one hand, this is the promotion of the most advanced technologies, although they do not offer anything super new, at least in Russia. In some technologies, in water quality, for example, we are ahead. On the other hand, FMC’s rapid advance into the Russian market risks monopolizing the market.” The loser in this case, according to Petrov, is the state: if 10 years ago about 30% of the cost of the hemodialysis procedure went abroad in the form of payment for consumables, now, after foreigners opened their own dialysis centers, 100% of the payment goes “ to the budget of a transnational corporation."

Evgeny Shilov notes that the quality of care in private dialysis centers varies, and it is higher in large foreign networks with their own internal standards. “It happens that businessmen think only about profit,” complains the country’s chief nephrologist. There have been cases where private centers were unable or even unwilling to help patients whose health condition deteriorated sharply during the course of dialysis. “Since the dialysis process often does not require the supervision of a doctor, the procedure in such centers became nursing; sometimes, an advanced patient even tightened the levers himself. But this is until the patient becomes heavier and turns from outpatient to inpatient,” says Shilov. Dialysis centers, the chief nephrologist emphasizes, must enter into an agreement with the hospital hospital, which, if necessary, will take over the treatment of the patient. And after a number of scandals, this practice was introduced everywhere.

At the same time, private companies are waiting for the professional community to develop parameters by which centers could be checked. According to Oleg Kotenko’s forecasts, the nephrology service will need one and a half to two years to do this, and the issue of tariffs can be resolved before the end of 2013.

results

Over the course of 6 years, 5942 patients were treated in the ICU after planned surgical interventions. 11 (0.2%) patients (9 men and 2 women) required RRT. The average age in the group was 59.4 (20–81) years, body weight was 79.3 (55–112) kg. The average length of stay of patients in the hospital was 40 (7–120) bed days, mortality in the study group was 45.5% ( n

=5).

RRT was mainly performed in patients with liver and biliary tract diseases ( n

=5). Bifurcation aortofemoral bypass surgery due to atherosclerotic lesions of the arteries of the lower extremities was performed in 3 patients. Due to gastrointestinal diseases, 2 patients were operated on, 1 patient underwent surgery on the spine.

All patients had concomitant diseases (Table 1).

Table 1. Concomitant diseases in patients with renal replacement therapy Diseases of the cardiovascular system were noted in 82% of patients, CKD was diagnosed in 46%.

The intraoperative period in 9 patients was uneventful. In 2 patients, an episode of ineffective blood circulation occurred during the operation: in one case, against the background of massive pulmonary embolism, in the other, against the background of acute cardiovascular failure.

In 8 (72.7%) patients, 1-3 reoperations were performed at various times after the main surgical intervention. The indications were complications: peritonitis, cholestasis, acute ischemia of the lower limb, intra-abdominal bleeding, suppuration of the postoperative wound, necrosis of the small intestine. In the postoperative period, the clinical condition of the patients worsened - the APACHE II score was 15.9 (5-36) points at the time of admission to the ICU and 28.9 (17-41) points at the time the decision was made to start RRT. The estimated probability of death on average for the group at the start of RRT was 63.5±23%. The SOFA score in 7 patients with sepsis worsened from 7.5 (4-11) to 14.5 (12-17) points.

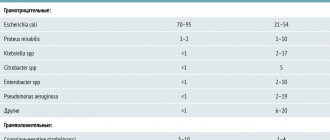

At the start of RRT, all patients were diagnosed with certain complications (Table 2).

Table 2. Complications upon initiation of renal replacement therapy

Multiple organ failure syndrome (MODS) with dysfunction of 4 or more organs and systems was observed in 9 out of 11 patients. The leading components of MODS were cardiovascular, respiratory, renal, and liver failure.

The main causes of AKI development were sepsis (7 cases), reperfusion syndrome (3), acute liver failure (1). RRT in 1 patient with sepsis was started on the 74th day after surgery due to the development of AKI against the background of pancreatic necrosis and sepsis, in the rest - on average on the 5th day. In 3 patients with reperfusion syndrome, RRT was required on the 2nd day, in a patient with acute liver failure - on the 3rd day.

By the start of RRT, patients had unstable hemodynamics with a tendency to hypotension, which required the use of vasopressors and cardiotonics. Norepinephrine support was provided to all patients with MODS at an average dose of 740 ng/kg/min (minimum dose 120 ng/kg/min, maximum dose 1800 ng/kg/min). In 7 patients, dopmin was used at an average dose of 3.4 mcg/kg/min (minimum dose 2 mcg/kg/min, maximum dose 4.5 mcg/kg/min). In 9 patients, the creatinine level was 1.5–1.9 times higher than the basal level over 48 hours of observation (KDIGO, stage 1), in 3 patients it was increased by more than 3 times (KDIGO, stage 3).

In 6 patients, RRT was started with continuous venovenous hemodiafiltration (CVVHDF) (mortality rate 66.7%), the duration averaged 72 (24-144) hours. In 2 of 3 surviving patients, therapy was continued in the form of daily hemodiafiltration sessions using an artificial kidneys lasting from 4 to 12 hours. In 5 patients, RRT was started with daily hemodiafiltration sessions on an artificial kidney with the same duration (mortality 40%).

On average, 6 patients were discharged from the hospital on the 42nd (15–111th) day from the start of RRT. The average duration of RRT was 20 (4–42) days. At discharge from the hospital, 3 of them had GFR more than 90 ml/min, 3 patients had a decrease in renal function by an average of 50% from the initial level (see figure).

Dynamics of glomerular filtration rate in patients at the time of discharge from hospital.

When analyzing possible predisposing factors and causes that led to a decrease in renal function, it was revealed that 2 patients had stage III CKD against the background of widespread atherosclerosis, 1 patient experienced intraoperative circulatory arrest with the development of cardiogenic shock.

Thus, in all electively operated patients with AKI in the postoperative period who require RRT, predisposing factors to its development have been identified: old age, chronic heart disease, arterial hypertension, diabetes mellitus, widespread atherosclerotic vascular lesions. Almost half of the patients were diagnosed with CKD. Only 2 patients had no intraoperative problems or repeated surgical interventions. All patients experienced postoperative complications that led to one of 3 main pathological conditions (sepsis, reperfusion syndrome, acute liver failure), which caused the development of AKI. Multiple organ failure syndrome was observed in 81.8% of patients. Only half of the surviving patients recovered renal function.

Market replacement therapy

According to representatives of the largest network of dialysis centers in Russia (and, perhaps, in the whole world) Fresenius Medical Care (FMC), there are no commercial clients in this area - all patients undergo hemodialysis procedures under compulsory medical insurance policies. “The tariff for outpatient hemodialysis in the Nizhny Novgorod region is 4820.06 rubles. That is, on average, treatment of one patient costs 750 thousand rubles per year,” Sergei Kurdaev, director of the FMC regional office in Nizhny Novgorod, gives an example.

Few people are able to shell out that amount of money each year from their pocket. The availability of OST in Russia is extremely low (see sidebar), and without private investors the state is unable to solve the problem with the number of dialysis places. Judging by the number of opening dialysis centers, serious hopes are pinned on public-private partnerships: in 2013, private companies have already opened centers in Penza, Ufa, Elista, Birobidzhan, St. Petersburg, Tyumen, Tula, and in the Kemerovo and Sverdlovsk regions. By the end of the year, private centers will open in at least six more regions of the country. The emergence of an increasing number of dialysis centers is an absolute plus, says Mikhail Gavrikov, chairman of the patient organization for nephrology and transplant patients “Right to Life”. And from the point of view of an entrepreneur, a visitor to an outpatient dialysis center is an ideal client, whose life and health depend on carefully following the schedule of procedures, and payment for the services provided to him is guaranteed by the state.

The only chance for a patient with chronic renal failure to get off the dialysis “needle” is a kidney transplant. “Then,” says Gavrikov, “the body begins to work and produce enzymes that will not need to be administered.” Gavrikov, who received a kidney transplant in 1998, considers transplantation to be a much less expensive type of RRT than dialysis: “Treatment costs about a million to one and a half rubles a year, transplantation costs about 890 thousand rubles. Plus, you need to take immunosuppressive drugs for a year, but their price is significantly lower than this amount.”

Doctors agree with the arguments of the chairman of the patient organization. The solution to the issue depends on the absence of a law on organ donation: doctors cannot take donor organs without the risk of incurring criminal liability for allegedly “black transplantation.” According to the chief nephrologist of Russia, out of 28 thousand patients on RRT, no more than 20% receive a kidney transplant, while half of the transplants are from closely related donations. In general, the vast majority of clients of dialysis centers do not yet have an alternative.

Now the content of compulsory health insurance tariffs varies in the regions, and there is no uniform calculation method. According to the interregional public organization “Nephro-League”, the cost of hemodialysis procedures can vary almost significantly between subjects of the Russian Federation. The average cost of dialysis is about 5 thousand rubles, although in Udmurtia, for example, the tariff is 3,300 rubles, and in the Omsk region - 6,677 rubles. “Whether dialysis will develop in this region or not largely depends on the tariff. If the tariff allows, dialysis will develop, capacity [availability of places. – VM] will increase,” says medical director of B. Braun Avitum Russland Clinics Valery Shilo. According to his estimates, the minimum tariff value that makes dialysis commercially attractive is about 4 thousand rubles per procedure (more for remote and hard-to-reach regions). Valery Shilo emphasizes that tariffs are often formed opaquely and illogically: “The region has switched to compulsory medical insurance. But how was the tariff determined? We divided the amount of money previously allocated by the number of patients and the number of procedures. It turned out roughly 4 thousand rubles for one procedure. Dialysis is developing, patients are accepted for dialysis without restrictions - there are no longer 100, but 150. But the same amount of money remains. And what is the region doing? Divides the same amount of money among a larger number of patients, and the tariff decreases. And the demands of patients are growing - they do not understand that tomorrow will be worse for them than yesterday. This technique is unacceptable."

Sometimes it happens differently: there are dialysis beds, but the regional budget does not have enough funds to fill them with patients. “There was a ready-made department in Ryazan, but no patients were sent – no money was allocated. In the Rostov region, until recently, there was a very difficult situation with access to dialysis,” says Valery Shilo. At times, lack of funding forced patients to move to neighboring cities and regions where dialysis centers operated. For example, patients from Rostov-on-Don went to live in the Krasnodar Territory - the compulsory medical insurance policy allowed treatment not at their place of permanent residence. Stavropol patients traveled to Karachay-Cherkessia, and when dialysis centers opened in Stavropol, Essentuki and Budennovsk, they returned. “This is a big advantage of single-channel financing - the opportunity to receive help in any subject of the Russian Federation,” says medical director B. Braun.

Moscow is one of the regions that have not yet switched to dialysis under compulsory medical insurance; treatment of patients here is paid for from the capital’s budget, the cost of the procedure is over 6 thousand rubles. In Moscow, there are 2,700 people on program dialysis, who are distributed in approximately equal proportions between private and municipal dialysis departments. The budget, according to the capital’s nephrologist Oleg Kotenko, is planned for a certain number of dialysis machines. Thus, it is easy to calculate the number of dialysis sessions that can be performed with this money. “Together with the Federal Compulsory Medical Insurance Fund we are developing a reasonable approach to tariffs,” says Oleg Kotenko. “Then foreign companies will have normal working conditions.”