home

Diagnostics

Cystoscopy

Cystoscopy with ureteral catheterization

Prices Reviews Our specialists Make an appointment

20.04.2020

Cystoscopy with catheterization of the ureter is performed to identify the cause of the disturbance in the outflow of urine from the kidney and to restore this outflow through the catheter. In most cases, such manipulation is performed urgently in case of persistent renal colic or obstructive pyelonephritis (inflammation of the kidney). The procedure is performed under sterile conditions using catheters of different sizes.

Research technique

Under sterile conditions, a cystoscope is inserted into the bladder and a diagnostic cystoscopy is performed. After which a thin catheter is inserted into the mouth of the ureter. The catheter insertion procedure takes place in a free rhythm, without violence. At the time of administration, the doctor observes the possible appearance of fluid or urine from the urethra, and visually analyzes its condition (color, consistency). If there is copious discharge of cloudy urine, we can conclude that the catheter is overcoming some kind of obstacle. When blood is discharged from the ureter, scarlet color suggests the presence of a tumor in the ureter.

Indications and Contraindications

Indications

: acute and chronic, urinary retention, the need for endourethral and endovesical administration of medicinal and radiopaque substances, determination of the capacity and tone of the bladder, evacuation of residual urine and determination of its quantity. K. m.p. is used for cystourethrography and obtaining urine from the bladder for laboratory research. Catheterization of the ureter and renal pelvis is indicated to determine the patency of the upper urinary tract, localize the obstruction, to separate urine from each kidney, perform retrograde ureteropyelography, eliminate urinary stasis, remove stones, bougienage, and administer drugs to the upper urinary tract.

Contraindications

- acute inflammatory processes of the urethra and bladder.

doctor

Specialized multidisciplinary clinic

Our staff consists of high-class doctors - members of the Russian and European Societies (EA).

We have a day hospital

We guarantee constant care for the patient and control over his recovery in the most comfortable conditions.

Low-traumatic treatment methods

We carry out operations with minimal intervention in the body using modern equipment of the new generation of intraoperative X-ray systems.

Evaluation of the effectiveness of kidney drainage methods for acute obstructive pyelonephritis

S.V. Shkodkin1,2, Yu.B. Idashkin1, V.V. Fentisov2, A.V. Lyubushkin2, A.A. Nevsky2 1 OGBUZ "Belgorod Regional Clinical Hospital of St. Joasaph"; Belgorod, Russia 2 Federal State Autonomous Educational Institution of Higher Education "Belgorod State National Research University"; Belgorod, Russia

Introduction

In urological practice, in order to restore the passage of urine from the upper urinary tract, long-term external (nephrostomy, pyelostomy) and internal (installation of a self-retaining catheter-stent in the ureter) drainage are routinely used [1-4]. Currently, there are no generally accepted indications for choosing a technique for drainage of the upper urinary tract for obstructive uropathy [1, 5]. Both external and internal drainage are associated with a number of disadvantages that affect the patient’s quality of life [1, 3, 4]. As a rule, the choice of method for restoring urinary passage remains at the discretion of the physician [1]. Internal drainage, due to the less invasiveness of the procedure, is much more often used by practicing urologists [5-7].

The advantages of the latter include the relative ease of installation and removal of the internal stent (both endoscopically and intraoperatively), the optionality of X-ray or ultrasound control, and the absence of external drainage. This improves quality of life and reduces the risk of nosocomial drainage infection. Therefore, internal drainage is used more widely and is recommended by many experts after endourological manipulations (nephro- and ureterolithotripsy, endouretero- and pyelotomy) on the upper urinary tract when performing reconstructive plastic surgery on the ureter and ureteropelvic segment, radical surgery for muscle-invasive bladder cancer [1, 3, 5, 8-9]. At the same time, there are also weaknesses of this method of restoring urine passage, namely the impossibility of endoscopic installation and removal of stents in some cases of urethral obstruction and pathology of the vesicourethral segment (strictures, tumors and urethral stones, benign hyperplasia and prostate cancer, sclerosis and cancer bladder neck), migration of the stent and its inadequate positioning when installed without radiological control, obstruction of the stent by inflammatory detritus, salts, blood clots due to anatomical restrictions on the diameter used and large length/diameter ratios, limited timing of internal drainage, which requires removal or replacement of the stent , the formation of vesicoureteral reflux with the development of reflux nephropathy and ascending infection, impaired motility and microcirculation in the stented ureter, leading to sclerotic changes in its wall even against the background of short drainage [10-13].

On the contrary, the disadvantages of puncture nephrostomy, in addition to the external drainage itself, include the risk of bleeding during the creation of access to the kidney, the need to use ultrasound and/or radiological control, and increased risks of contamination with nosocomial microflora [9, 14].

The undoubted advantages of this method are a short drainage channel, the possibility of installing a drainage of adequate diameter, and the procedure can be performed regardless of the level and cause of supravesical obstruction or obstruction of the vesicourethral segment [2, 7].

Purpose of the study. To evaluate the effectiveness of internal stenting (IS) and puncture nephrostomy (PN) as methods of temporary drainage of the upper urinary tract in acute obstructive pyelonephritis.

Materials and methods

During 2012-2017 We observed 156 patients of both sexes aged from 25 to 74 years with a clinical picture of acute obstructive pyelonephritis against the background of urolithiasis, in whom no purulent-destructive kidney damage was detected at the preoperative stage, and in order to restore the passage of urine, VS or PN were performed. The first group of the study included 125 patients who underwent PN, the second group included 31 patients who underwent VS with a ureteral stent. Both groups were comparable in gender, age and time spent in hospital before kidney drainage; the side of the lesion did not influence the choice of urine diversion technique (Table 1).

Table 1. Characteristics of observation groups

| Observation group | Age, years | Gender, husband/wives | Affected side, right/left | Preoperative period, hour |

| First group, Group I (n=125) | 50,6±13,8 | 56/44 | 44/56 | 2,1±1,3 |

| Second group, Group II (n=31) | 43,2±18,3 | 53,8/45,2 | 48,4/51,6 | 3,6±1,4 |

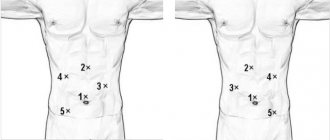

In the first group, the preoperative febrile period and leukocytosis were significantly longer: 5.5 ± 1.3 days and 18.1 ± 2.8 x 109/l, while in the second group the same indicators were 2.1 ± 1.4 days and 9.5 ±3.1x109/l, respectively (p<0.05), the volume of the kidney and the thickness of the parenchyma on the affected side were not statistically different in both observation groups (Fig. 1). PN was performed under local infiltration anesthesia with combined ultrasound and x-ray control, VS - with instillation of lubricant into the urethra and x-ray control. In both groups, half an hour before the start of the drainage procedure, ataralgesia was performed (Promedol 2% - 1.0 and Relanium 0.5% - 2.0 intramuscularly). In the postoperative period, along with the assessment of clinical manifestations, laboratory, bacteriological and ultrasound monitoring were carried out on the 1st, 5th and 10th days.

Figure 1. Initial clinical and laboratory data. 1 – febrile period, days; 2 – leukocytosis, 109/l; 3 – relative neutrophilia, %; 4 – kidney volume, cm3; 5 – parenchyma thickness, mm; 6 – anteroposterior size of the pelvis, mm. *—differences are statistically significant, p<0.05.

The data obtained as a result of the study were processed using Statistica 6.0 software on the Windows XP operating platform. When analyzing population data, average indicators were calculated (arithmetic mean (xsr); median (Me); mode (Mo)), absolute indicators of variation (range of variation (R); linear mean deviation (dsr); dispersion (σ2); standard deviation (σ). The studied indicators, which have a normal distribution, are given in their average value with a mean square error: M ± σ. To establish the statistical significance of the differences in the indicators of the main and control groups, the probability was calculated using the Student distribution. If the probability is less than 0.05, the difference was considered statistically reliable.

results

There were no reasons for refusal to perform PN, as well as traumatic complications from the drained kidney in the first group. Moderate gross hematuria due to drainage, which did not require blood or plasma transfusion, occurred in 47 (37.6%) patients and was relieved by conservative hemostatic therapy on 2.2±0.5 days. The first group included 4 (16%) patients with stones of the juxtavesical ureter who failed to undergo VS. The diameter of the installed drainage was determined by the clinical situation and the size of the renal cavity system. J-nephrostomies 12 and 14 Ch were used, and in the presence of purulent urine with detritus, Nelaton catheters 16-22 Ch, the average diameter of the installed nephrostomy was 17.4±3.2 Ch. The next day, against the background of increasing intoxication, 1 (0.8%) patient of the first group was operated on. During inspection of the kidney, multiple apostemes and carbuncles were identified; taking into account the severity of the systemic inflammatory response syndrome, the patient's age of 74 years and the preservation of the contralateral kidney, nephrectomy was performed.

As mentioned above, 4 patients who failed to perform VS were not included in the second group. For drainage, jj-stents 6 and 8 Ch were used, which averaged 6.26±0.68 Ch. Gross hematuria caused by the cystic end of the stent in this group was noted on days 2.7±1.8 after stenting in 13 (41.9%) patients and often occurred throughout the entire observation period, which amounted to 6.8±2.5 days. This complication required hemostatic and analgesic therapy, as well as the prescription of alpha-blockers, which, however, was not accompanied by a significant clinical effect. Gross hematuria and negative clinical and laboratory dynamics, manifested in the progression of pyelonephritis, became the reason for open revision of the kidney in 5 (16.1%) patients. In addition, inadequate stent performance (retention changes in the collecting system with an empty bladder according to ultrasound) was the reason for switching to PN in another 6 (19.4%) patients. Thus, a 10-day period of drainage was observed in 124 (99.2%) patients of the first and 20 (64.5%) patients of the second group (Table 2).

Table 2. Complications of kidney drainage methods

| Observation group | First group | Second group |

| Number of patients included in the study | 125 | 31 |

| Impossibility of carrying out a drainage procedure, abs./% | 0 / 0 | 4 / 11,4* |

| Progression of pyelonephritis, abs./% | 1 / 0,8 | 11 / 35,5* |

| The need for open revision of the kidney, abs./% | 1 / 0,8 | 5 / 16,1* |

| Frequency of gross hematuria, abs./% | 47 / 37,6 | 13 / 41,9 |

| Duration of gross hematuria, days | 2,2±0,5 | 6,8±2,5* |

| Irritative symptoms, abs./% | 0 / 0 | 18 / 58,1* |

| Clinic of PMR, abs./% | 0 / 0 | 9 / 29,0* |

| Duration of fever, days | 1,8±0,5 | 5,5±2,8* |

| Number of patients remaining in the study, abs./% | 124 / 99,2 | 20 / 64,5* |

Notes: * – the differences are statistically significant, p <0.05 Comments: * – the differences are statistically significant, p <0.05

In our observations, there were no cases of migration of nephrostomy drains and internal stents. The adequacy of their drainage function was assessed based on ultrasound, and if positioning control was necessary, survey urography was performed.

Clinically, the fever in group I was stopped on 1.8±0.5 days, and in group II this figure was 5.5±2.8 (p<0.05) (Table 2). In the second observation group, 18 (58.1%) patients complained of irritative symptoms of varying severity. 9 (29.0%) patients had pain in the lower back associated with miction. No such complications were noted in the first observation group.

Table 3. Microbiological spectrum of pathogens of acute obstructive pyelonephritis

| Observation group | First group, Group I (n=124) | Second group, Group II (n=20) | ||

| Number of crops | 372 | 60 | ||

| Number of strains | 417 | 73 | ||

| abs. | % | abs. | % | |

| Bacterial associations | 45 | 12,1 | 10 | 16,7 |

| Multidrug resistance | 286 | 68,5 | 53 | 72,6 |

| Escherichia coli | 145 | 34,8 | 24 | 32,9 |

| Klebsiella spp. | 79 | 18,9 | 12 | 16,4 |

| Enterococcus faecalis | 71 | 17 | 15 | 20,5 |

| Pseudomonas spp. | 37 | 8,9 | 9 | 12,3 |

| Proteus spp. | 51 | 12,2 | 6 | 8,2 |

| S. aureus | 21 | 5 | 3 | 4,1 |

| Enterobacter spp. | 8 | 1,9 | 2 | 2,7 |

| Others | 5 | 1,2 | 2 | 2,7 |

Laboratory control in the first group of observation revealed a significant decrease in neutrophilic leukocytosis of the rod-nuclear shift from the fifth day of observation relative to the initial indicators (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. Laboratory and instrumental dynamics of acute obstructive pyelonephritis: a – dynamics of leukocytosis; b – dynamics of kidney volume

In group II patients, no similar trend was noted; a statistically insignificant increase in leukocytosis was recorded on the fifth and tenth days. By the end of the observation period, the level of leukocytes in the blood of patients in the first group was significantly lower than the comparison group (p <0.05). Laboratory urine test parameters did not have statistically significant differences between the groups at this observation period.

Ultrasound monitoring of group I revealed statistically significant dynamics of decrease in kidney volume relative to the initial values, while the kidney volume in the comparison group did not statistically change (Fig. 2), which led to significant differences in this indicator by the end of the observation period (p0.05). In group II, ultrasound signs of vesicoureteral reflux were noted: the anteroposterior size of the pelvis with a full bladder was 37.1±5.8 mm (p<0.05).

Discussion

Subject to adequate renal puncture technique and the use of combined (ultrasonic and radiological) control, PN is a safe method of kidney drainage in acute obstructive pyelonephritis, ensuring the installation of a drainage of adequate diameter, which allows one to obtain better results in relieving pyelonephritis in comparison with the VS group. The internal stent did not provide adequate drainage in 11 (32.4%) patients of the second group, who had to resort to additional surgical procedures. But in the remaining cohort of patients, ultrasound findings of urostasis were noted, associated both with a small diameter of the drainage and with vesicoureteral reflux. This was the reason for the long-term persistence of inflammatory changes, manifested by systemic leukocytosis and long-term persistence of an increase in the volume of the affected kidney in this observation group. In the first observation group, no irritative symptoms or torpid hematuria were noted, which ensured better patient tolerance of external drainage.

Noteworthy is the high degree of bacterial contamination and the frequency of detection of antibiotic-resistant microflora. The latter is due to the fact that 53.6% of patients who had previously operated on the urinary tract participated in the study and our results do not contradict the literature data. The high degree of bacteriuria obtained in the first group was due to both the initial laboratory-confirmed more pronounced inflammatory changes and the material sent for research. That is, during PN, urine obtained during puncture of the abdominal cavity system of the affected organ was sent for bacteriological examination, while after VS, a washout from the bladder was taken, which contained, among other things, urine from the contralateral kidney and the remains of irrigation fluid. The increase in the number of resistant flora in a short time interval is due to the selection of strains with existing antibiotic resistance. The presence of infected stones and drainages most likely caused the persistence of bacteriuria even in the absence of clinical manifestations of pyelonephritis.

conclusions

- Puncture nephrostomy provides more effective and safe kidney drainage in patients with acute obstructive pyelonephritis.

- Temporary use of an external drain is associated with better quality of life outcomes compared with an internal stent.

- The use of an internal stent for acute obstructive pyelonephritis prolongs inflammatory changes in the kidney and in 32.4% of cases will require additional interventions compared to puncture nephrostomy.

- Despite antibacterial therapy, both methods of drainage do not contribute to the elimination of pathogens within 10 days of acute obstructive pyelonephritis.

Literature

- Doronchuk D.N., Trapeznikova M.F., Dutov V.V. Choosing a method of drainage of the upper urinary tract in case of urolithiasis. Urology. 2010;3:7-10.

- Auge BK, Sarvis JA, L'Esperance JO, Preminger G. Practice patterns of ureteral stenting after routine ureteroscopic stone surgery: A survey of practicing urologists. J. Endourol. 2007;21(11):1287-1291. doi: 10.1089/end.2007.0038

- Preminger GM, Tiselius HG, Assimos DG et al. EAU/AUA Nephrolithiasis Guideline Panel. 2007.

- Alyaev Yu.G., Rapoport L.M., Tsarichenko D.G., Stoilov S.V., Bushuev V.O. Renal stenting for ureterohydronephrosis in patients with large prostate hyperplasia. Androl. and genital. hir. 2008;3:43-44.

- Trapeznikova M.F., Dutov V.V., Bazaev V.V., Doronchuk D.N. On the issue of the need for stenting of the upper urinary tract after uncomplicated contact ureterolithotripsy. Materials of the First Russian Congress on Endourology (Moscow, June 4-6, 2008). M., 2008:257-258.

- Alyaev Yu.G., Rudenko V.I., Gazimiev M.A. and others. Types of ureteral stenting after contact ureterolithotripsy. Materials of the First Russian Congress on Endourology (Moscow, June 4-6, 2008). M., 2008:126-127.

- Chew BH, Knudsen BE, NottL, Pautler SE, Razvi H, Amann J, Denstedt JD. Pilot study of ureteral movement in stented patients: First step in understanding dynamic ureteral anatomy to improve stent discomfort. J. Endourol. 2007;21(9):1069-1075. doi: 10.1089/end.2006.0252

- Guliev B.G. Reconstructive operations for organic obstruction of the upper urinary tract: Dissertation.... Dr. med. Sci. - St. Petersburg, 2008.

- Kogan M.I., Shkodkin S.V., Idashkin Yu.B., Lyubushkin A.V., Miroshnichenko O.V. Evaluation of the effectiveness of various methods of kidney drainage. Medical Bulletin of Bashkortostan. 2013;2:82-85.

- Novikova E.G., Teplov A.A., Smirnova S.V., Onopko V.F., Rusakov I.G. Ureteral strictures in patients with cervical cancer. Russian journal of oncology. 2009;3:28-34.

- Wise I.S. Functional states of the upper urinary tract in urological diseases: Diss.... Dr. med. Sci. -M., 2002.

- Chepurov A.K., Zenkov S.S., Mamaev I.E., Pronkin E.A. The effect of long-term drainage of the upper urinary tract with ureteral stents on the functional abilities of the kidney. Andrology and genital surgery. 2009;172-1721.

- Doronchuk D.N., Trapeznikova M.F., Dutov V.V. Assessment of the quality of life of patients with urolithiasis depending on the method of drainage of the upper urinary tract. Urology. 2010;2:14.

- Chepurov A.K., Zenkov S.S., Mamaev I.E., Pronkin E.A. The role of upper urinary tract infection in patients with long-term drainage with ureteral stents. Andrology and genital surgery. 2009;173-173.

The article was published in the journal “Bulletin of Urology” No. 1 2021, pp. 27-34

Topics and tags

Lower urinary tract infections

Urinary tract infections

Magazine

Bulletin of Urology No. 1 2018

Comments

To post comments you must log in or register

Our partners

Phlebology Clinic First Phlebological Center

Phlebology Clinic First Phlebological Center.

Treatment of varicose veins by leading specialists from Russia using the most advanced equipment. The head of the clinic is Viktor Nikolaevich Lobanov, a vascular surgeon and phlebologist. The clinic’s doctors have more than 20 years of experience, which makes it possible to treat chronic diseases, as well as perform operations even at the most severe stages of venous disease. The Phlebology Center is located at: Moscow, st. Dmitry Ulyanov, 31. Phone: +7(495) 967-94-42.

Patients of our urology clinic are provided with preferential conditions for consultations, diagnostics and further treatment.