Urolithiasis is a common urological disease. For many years it has been at the forefront of urology. This article presents the etiology, diagnosis, medical and interventional treatment of urinary tract stones.

Urolithiasis is a disease that has existed for thousands of years. Archaeological studies have shown the presence of deposits in the urinary tract of Egyptian mummies estimated to be around 7,000 years ago. Removing bladder stones was one of the first surgical procedures performed in ancient times.

The last two decades have brought significant progress in understanding the etiology, diagnosis and, above all, treatment of urolithiasis. The development of endourology and stone crushing equipment has significantly reduced the number of operations performed for this disease.

Epidemiology of the disease - how common are stones in the urinary system?

The content of the article

Urolithiasis occurs in approximately 2% of the population. Most often, stones are discovered after 30 years. Men suffer from this disease three times more often than women.

People who have an episode of renal colic have about a 15% chance of having another episode within 3 years, and a 30-50% chance of having another episode within the next 15 years. As a rule, urolithiasis is a long-term disease, with an average period of 9 years between attacks.

Urolithiasis disease

Etiology and pathogenesis of urolithiasis

Urinary stones are formed as a result of complex physical and chemical processes. They try to explain the mechanism of their formation using the following theories:

- Theory of supersaturation and crystallization.

When the solubility product of a given substance is exceeded, the solution becomes oversaturated. Nucleation and subsequent aggregation result in the formation of tiny crystals, which then form urinary deposits. - The phenomenon of epitaxy

. Epitaxy is the ability to form crystals of one substance in a supersaturated solution of another. For example, adding uric acid crystals to a supersaturated solution of calcium oxalate causes deposition of the latter on the uric acid nucleus. - No crystallization inhibitors

. During the day, urine is often a supersaturated solution, but due to the presence of crystallization inhibitors, it does not form deposits. Inhibitors can further inhibit crystal growth after crystal formation and aggregation. Crystallization inhibitors include: Mg, Zn, citrates, while crystal growth and aggregation inhibitors include: pyrophosphates and acid mucopolysaccharides. - Organic matrix theory.

Deposition of crystals on a proteinaceous substance, which in some types of sediment can constitute up to 65% of the sediment mass. High levels of protein are characteristic of urolithiasis associated with urinary tract infections, mainly bacteria from the Proteus group.

The formation of stones in the urinary tract is determined by three groups of factors:

- Systemic factors - affect the chemical composition and physical characteristics of urine, for example, gout or tubular acidosis.

- Individual properties of the kidneys and urinary tract - for example, renal calcification, subpyelitis, urinary tract infection with urease-positive bacteria.

- Environmental conditions, for example, high ambient temperature, protein-rich diet, prolonged immobilization.

In the first group, urolithiasis is more often bilateral, multifocal and recurrent, then we are talking about systemic urolithiasis, in the second group the lesion usually affects one organ - the kidney or bladder, and only relapses occur in it. In the third group, large populations may be affected by urolithiasis. The most favorable condition for urolithiasis is the presence of three factors in one person.

The formation of stones in the urinary tract is a complex biophysical process, as evidenced by the formation of deposits. In most patients, the pathogenesis of nephrolithiasis is based on disorders of calcium-phosphate metabolism and oxalic acid metabolism, and much less often - purine and amino acid metabolism.

Calcium oxalates form most of the deposits in the urinary system. Almost 75% of stones contain calcium, and 30 to 60% of patients with urolithiasis have hypercalciuria (daily urinary calcium excretion greater than 6.25 mmol (250 mg) in women and 7.5 mmol (300 mg) in men).

Calcium oxalates

Hypercalciuria occurs in various disease conditions. This may be caused by excessive absorption of calcium from the gastrointestinal tract, excessive mobilization from the skeletal system, or impaired renal tubular reabsorption.

A. excessive absorption from the gastrointestinal tract:

- excessive intake of foods rich in calcium,

- hypervitaminosis D.

B. excessive mobilization of calcium from bones:

- hyperparathyroidism;

- hypervitaminosis D;

- overactive thyroid gland.

Paget's disease

- long-term immobilization;

- tumor metastases.

C. reabsorption defect:

- tubular acidosis;

- hyperaldosteronism;

- increased consumption of Na, Mg ions;

- loop diuretics – furosemide, ethacrynic acid.

Oxalic acid, along with hypercalciuria, is the most important factor in the formation of urolithiasis. Under physiological conditions, more than 90% of oxalic acid excreted in urine is a product of intermediate metabolism of amino acids and carbohydrates.

Hyperoxaluria occurs as a result of increased endogenous production and excessive absorption from the gastrointestinal tract. Some evidence suggests that hyperoxaluria promotes plaque formation 10 times more than elevated calcium levels.

A. primary increase in biosynthesis:

- congenital deficiency of glyoxylic acid alpha-ketoglutarate ligase,

- congenital deficiency of D-glycerate dehydrogenase,

- taking oxalic acid precursors (vitamin C, ethylene glycol).

B. overabsorption in the gastrointestinal tract:

- insufficient intake of calcium from food,

- excessive intake of oxalic acid,

- chronic inflammatory bowel diseases (ulcerative colitis, Crohn's disease).

Uric acid, excreted by the kidneys, is a product of purine metabolism. Gout accounts for approximately 5% of all deposits. Urine concentration and pH play a big role in stone formation. At pH 4.5, about 95% of the uric acid present in urine is poorly soluble, and solubility increases with increasing pH.

Hyperuricosuria can be caused by the following factors:

A. Endogenous hyperproduction of uric acid: increased cellular metabolism (proliferation of tumor cells, intensive cancer chemotherapy).

B. Excessive excretion of uric acid in the urine: uricosuric drugs (salicylates, thiazides), diet high in purines.

C. Increased concentration in urine with normal daily secretion of uric acid:

- dehydration (diseases of the gastrointestinal tract);

- excessive acidification of urine (prolonged diarrhea, loss of alkalis through intestinal fistulas).

Cystine stones make up about 1%. Formed in patients with a congenital defect in the resorption of cystine and dibasic amino acids (arginine, ornithine) in the small intestine and renal tubules.

Struvite stones (15%) form in alkaline urine due to contamination by urea-positive bacteria, which break down urea into ammonia. Under the influence of high urine pH (above 7.0), magnesium ammonium phosphate and apatite carbonate precipitate. Microorganisms containing urease include: Proteus vulgaris, Klebsiella, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Serratia, Providensia, Enterobacter, Staphylococcus.

Struvite stones

These microorganisms also secrete mucus, which promotes good adhesion to the epithelium and protects it from the effects of antibiotics. This mucus is the protein framework of struvite stones. Struvite never forms in sterile urine and is a major component of foundry stones.

Stones in the urine can vary in size, from 1 mm or less in diameter, and are excreted in the urine in the form of so-called sand, up to large stones in the collecting system or in the bladder.

The shape, size and consistency of stones depend to some extent on their chemical composition and the proportion of the protein framework. The hardest are calcium oxalate and cystine stones, phosphate deposits, especially struvite, are brittle, and uric acid is the softest.

In cross section, the stone can have a layered or spoke structure. Very often the middle part of the stone, the so-called cross-section of the core, has a different appearance and chemical composition than the shell. The chemical composition of the testicle may indicate a metabolic cause of urolithiasis, which is important for preventing recurrence. The mantle layer reflects the characteristics of the environment in the calyces and pelvis. Chemically pure stones, most commonly calcium oxalate and uric acid stones, account for about 42%. About 45% are two-component stones, the rest are three-component.

Calcium oxalate deposits are most often single, about 1-2.5 cm in size, with a smooth or plum-colored surface. Mostly smooth stones with different chemical compositions. Cystine deposits are tan, waxy, light yellow or gray phosphate deposits and dark brown uric acid deposits.

Testing the chemical composition of the stones can help prevent recurrence. Research into the metabolic processes that lead to increased urinary excretion of stones may play a more important role.

Modern treatment of urolithiasis: focus on improving outcomes

A.G. Martov, D.V. Ergakov

Information about authors:

- Martov A.G. – Doctor of Medical Sciences, Professor, Head of the 2nd Urological Department of the State Budgetary Institution of Healthcare of the City Clinical Hospital named after D.D. Pletneva, Head of the Department of Urology and Andrology, FMBC named after Burnazyan, FMBA of the Russian Federation, RSCI AuthorID 788667

- Ergakov D.V. – Candidate of Medical Sciences, urologist of the 2nd urological department of the State Budgetary Institution of Healthcare of the City Clinical Hospital named after D.D. Pletneva, Associate Professor of the Department of Urology and Andrology, FMBC named after. Burnazyan FMBA RF

DOI 10.29188/2222-8543-2020-12-3-65-70

INTRODUCTION

Urolithiasis is a nosology, the frequency of which is steadily increasing in developed countries. The reasons for the increase in the incidence of urolithiasis are the sedentary lifestyle of patients, the predominant consumption of high-calorie foods, concomitant endocrine diseases and dysfunction of the gastrointestinal tract, diseases of internal organs, which together lead to an increase in the incidence and prevalence of urolithiasis [1, 2].

Over the past two decades, there has been a revolutionary change in therapeutic approaches to the management of patients with urolithiasis. In addition to the increasing frequency of use of endourological treatment methods, the effectiveness of extracorporeal lithotripsy is improving, and modern methods of lithokinetic therapy are being developed [3, 4]. Every year, innovative technological solutions appear in one type of surgical treatment or another, as well as new medications and complex dietary supplements designed to increase the effectiveness of the treatment. Currently, only a comprehensive, often individual, approach to treating a patient seems optimal, consisting not only of minimally invasive removal or fragmentation of the stone without significant trauma to the renal parenchyma, but also including anti-inflammatory treatment designed to eliminate local factors for the recurrence of stone formation (normalization of urine pH , increased diuresis) and providing a better quality of life for the patient [5-7].

Currently, conservative treatment is used in patients with small (up to 5 mm) kidney stones in the absence of urodynamic disturbances; this approach is associated with minimal chances of developing obstructive complications of urolithiasis. The main fears of this category of patients are associated with the fear of developing renal colic and the possible ineffectiveness of the treatment [8-10].

Kidney stones up to 1 cm in most cases, when indications for their surgical treatment are identified, are treated as the method of choice using extracorporeal lithotripsy, which allows a positive effect to be achieved in the vast majority of patients. The main problems of this treatment method are associated with its possible ineffectiveness (lack of stone fragmentation) or with the failure of already crushed stone fragments to pass [11-12].

Larger stones, with the exception of large (>2 cm) and staghorn stones, are increasingly being treated using either flexible transurethral fibroureteropyeloscopy or minimally invasive versions of percutaneous nephrolithotripsy (mini- and micropercutaneous nephrolithotripsy) [13-15]. Increasingly, combined operations are described, performed from two approaches with the patient in the supine position, allowing not only to completely rid the patient of stones, but also to avoid inflammatory complications associated with the duration of the operation in conditions of increased intrapelvic pressure [15].

All of the above factors determine the emergence of new non-drug methods, which include dietary nutrition and lifestyle changes, which urologists could recommend to patients for a long period in order to increase diuresis after surgery to evacuate stone fragments and quickly normalize the composition of urine [16] .

Successful foreign experience in the use of the Renalof® complex in the conservative treatment of urolithiasis, better passage of fragments after external and transurethral lithotripsy, was one of the factors for its use after minimally invasive operations and metaphylaxis of stone formation [16-19].

Renalof® is a biologically active complex, which includes an activated extract of the herb Agropyron Repens and mannitol, which are widely known and used for the metaphylaxis of urolithiasis, as well as as part of the complex therapy of chronic pyelonephritis [16].

The purpose of the study was to determine the frequency of stone-free patients after conservative therapy, external and contact ureterolithotripsy, as well as to study the effectiveness and safety of the Renalof® complex in patients with urolithiasis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

From November 2021 to March 2021 on the basis of the State Clinical Hospital named after. D.D. Pletnev treated 170 patients (82 men and 88 women) aged from 23 to 84 years with kidney stones. In accordance with the goals and objectives of the study, the entire group of patients was divided into three groups. The inclusion criteria for the study were: informed consent, absence of decompensated diabetes mellitus, confirmation of the diagnosis of stone by computed tomography, any location in the kidney other than the calyx of the lower segment, and completion of a follow-up examination after 1 month to assess the effectiveness of treatment. Exclusion criteria were the patient's refusal to participate in the study, an allergic reaction to the components of the complex, and failure to appear for a follow-up examination.

Depending on the use of the Renalof® complex in the diet of patients, each group of patients was divided into two subgroups. The complex was taken 3 times a day, 1 capsule, for 1 month after the appointment of treatment or the patient’s discharge from the hospital after one or another type of surgical treatment.

The first group included 27 patients with kidney stones up to 5 mm, who were prescribed conservative lithokinetic therapy. 11 patients from this group additionally took the Renalof® complex, 16 received standard therapy. As criteria for the effectiveness of the treatment, the frequency of absence of stones, the frequency of leukocyturia (leukocytes more than 10), urine pH before and after treatment, the level of diuresis according to urination diaries, and quality of life according to the visual analogue scale were assessed.

The second group of patients consisted of 74 patients after extracorporeal calico-(pielo)lithotripsy performed for kidney stones from 6 to 10 mm. 28 patients took the dietary supplement Renalof® as part of their dietary recommendations, 46 patients received standard anti-inflammatory therapy (canephron 2 tablets 3 times a day or furagin 2 tablets 3 times a day). In this group of patients, the same criteria were used as in the first group.

The third group of patients included 69 patients after transurethral fibrocalico(pyelo-)lithotripsy for stones ranging in size from 11 to 20 mm. 33 patients took additional Renalof®, 36 patients took standard anti-inflammatory treatment. A feature of this group of patients was the presence of an internal stent after surgery; therefore, we did not use the degree of leukocyturia and urine pH as criteria for the effectiveness of treatment in this group of patients [8].

Recruitment into the main group was carried out prospectively, and into the control group - partially retrospectively, including patients who repeatedly visited the clinic to remove internal stents and conduct follow-up examinations regarding previously performed surgical interventions.

To assess the condition, a follow-up examination was performed 1 month after surgery, which included filling out a visual analogue scale (VAS), urination diaries, control ultrasound of the urinary system, control urine analysis and computed tomography of the kidneys without contrast. Information on the quality of life in patients after surgery on the upper urinary tract was obtained using a visual analogue scale, which was filled out by patients, with “0” being considered an absolutely unacceptable quality of life, and “100” being an excellent quality of life.

The primary endpoint of the study was to estimate the stone-free rate 1 month after conservative or surgical treatment. Secondary end points of the study were assessment of quality of life according to VAS, leukocyturia level, diuresis and urine pH.

The results obtained were entered into Microsoft Excel® and subjected to standard statistical processing. The significance of intergroup differences was determined using Fisher's test. Differences were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05.

RESULTS

The first part of our study was devoted to comparing two groups of patients with kidney stones up to 5 mm, who received conservative therapy aimed at spontaneous stone passage.

The results of treatment of patients of the first group are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Results of treatment of patients of the first

| Indicator | Major group (n = 11) Major group | Control group (n = 16) Control group |

| Departure of the stone | 9 (81,8%)* | 7 (43,7%) |

| Leukocyturia (L>10) Leukocyturia (L>10) | 2 (18,2 %) | 9 (56,3 %)* |

| Visual analog scale | 74±19 | 52±10 |

| Daily diuresis, l Daily diuresis, l | 3,3±0,4 | 2,8±0,4 |

| pH of urine pH of urine | 6,8±0,6* | 5,2±0,7 |

* p (Fisher's test) < 0.05 * p (Fisher's test) < 0.05

From the data in Table 1 it follows that in the first group stones passed spontaneously in 9 patients from the first group and in 7 patients from the second group, and the differences were statistically significant. Leukocyturia was noted in 2 patients from the first group and 9 from the second, which was also statistically significant. The differences in quality of life and daily diuresis were not statistically significant, however, in general, in the first group the quality of life was higher and daily diuresis was slightly higher. The acidity of urine was within normal limits in patients of the first group, and in the second group the pH was statistically significantly lower.

The second part of our study included 74 patients with kidney stones up to 1 cm in size who underwent extracorporeal lithotripsy. In 62 patients the stones were in the pelvis and in 12 in the calyces (upper segment - 5, middle segment - 7). The main group, where Renalof® was additionally prescribed, included 28 patients, and the control group - 46 patients. Patients with unfavorable anatomical factors (long and narrow calyx neck and lower segment calyx) were not included in the study.

The use of the Renalof® complex in complex therapy after extracorporeal lithotripsy made it possible to statistically significantly increase the frequency of stone passage from 54.3% to 75%, reduce the frequency of leukocyturia by 25% compared to the control group of patients, and increase daily diuresis to 3.2 liters in the main group from 2.8 l - in the control group (Table 2). In addition, urine pH during the use of Renalof® in the main group was statistically significantly higher than in the control group.

Table 2. Results of treatment of patients of the second group

| Indicator _ | Major group (n = 28) Major group | Control group (n = 46) Control group |

| The discharge of stone fragments | 21 (75%)* | 25 (54,3%) |

| Leukocyturia (L>10) Leukocyturia (L>10) | 7 (25 %) | 23 (50 %)* |

| Visual analog scale | 76±21 | 53±12 |

| Daily diuresis, l Daily diuresis, l | 3,2±0,3 | 2,8±0,4 |

| pH of urine pH of urine | 6,7±0,5* | 5,3±0,7 |

* p (Fisher's test) < 0.05 * p (Fisher's test) < 0.05

The third part of our study was devoted to the results of treatment of 69 patients who underwent transurethral contact pyelocalicolithotripsy. The difficulty of correctly assessing the results in this category of patients is due to the fact that after the operation the kidney was drained with an internal stent, so a reliable assessment of the presence of leukocyturia and urine pH in this group was not carried out. On the other hand, laser stone fragmentation was performed in these patients. We used a U2 Fiberlase thulium laser lithotripter; crushing was carried out in fine-dusting mode, so the size of the fragments did not exceed 1 mm and assessment of the lithokinetic effect of the Renalof® complex in this clinical situation was difficult. Table 3 shows the results of treatment for this group of patients. 33 patients were additionally prescribed the Renalof® complex, the results of treatment of 36 patients were used as a control group.

Of the main group, complete passage of stone fragments was detected in 28 (84.8%) patients and in 21 (58.3%) of the control group. This difference was statistically significant.

Table 3. Results of treatment of patients of the third

| Indicator | Major group (n = 33) Major group | Control group (n = 36) Control group |

| The discharge of stone fragments | 28 (84,8%)* | 21 (58,3%) |

| Visual analog scale | 64±21 | 41±14 |

| Daily diuresis, l Daily diuresis, l | 3,5±0,5 | 2,8±0,4 |

* p (Fisher's test) < 0.05 * p (Fisher's test) < 0.05

We have not observed any cases of discontinuation of the Renalof® complex due to the development of adverse events that could be associated with the use of this complex. Analysis of complications of surgical treatment did not reveal significant differences between groups.

DISCUSSION

Clinical experience with Renalof® has been assessed in several studies. The first clinical study examined the use of the complex in 78 patients with urolithiasis. The main group included 41 patients who were prescribed the Renalof® complex as an auxiliary dietary recommendation [17]. The authors demonstrated the following positive qualities of the complex: the possibility of partial litholysis of oxalate stones, an increase in urine pH due to an increase in the excretion of citrates in the urine. The average stone sizes were 0.7 and 0.6 cm, respectively. Patients from group 1 received Renalof 2 capsules 2 times a day. During the study, blood and urine tests, kidney ultrasound, and X-ray examination were monitored. The course of treatment for all patients in both groups was 3 months. In the main group of patients, by the end of the 2nd week of taking the Renalof® complex, there was an improvement in well-being in the form of a decrease (in 27) and absence of pain (in 14). Dysuric phenomena were stopped on the 9th day of taking the drug. In group 1, a decrease in stone size was observed in 22 patients, which amounted to 53.6%. Passage of stone fragments was observed in 17 (41.4%) patients. In group 2, a decrease in the size of the stone was observed in 7 (18.4%) patients, spontaneous passage in the form of sand - in 9 (23.6%) patients. Improvement in laboratory parameters in the form of a decrease in leukocyturia, erythrocyturia, bacteriuria, oxaluria was significantly more diagnosed in the main group.

Another study involving Renalof® was also conducted in Kazakhstan, and was aimed at studying the auxiliary role of Renalof® in patients after external nephrolithotripsy. 14 patients from the main group, who underwent remote stone destruction, were prescribed Renalof® as a dietary recommendation, 11 patients made up the control group. As a result of the use of Renalof®, a statistically significant increase in the efficiency of crushing was noted after the first session from 51.6% to 79.6%, the effectiveness of the second crushing was the same, the third crushing was not needed by any patient from the main group and was required by 19.6% of patients from the control group groups. The authors noted a good effect from the additional administration of the Renalof® complex [7, 16].

Another study was conducted in Indonesia in 2011, which analyzed the results of treatment of 30 patients with kidney stones up to 20 mm (2 cm) in size. Renalof® was prescribed 1 capsule 3 times a day for 1 month. The authors noted an additional effect from the administration of Renalof® in the form of normalization of the level of excretion of calcium and uric acid in the urine [18].

Another work studying the effect of Renalof® in patients with urolithiasis was published in Cuba in 2012. 110 patients were randomly selected to receive Renalof® complex (n = 52) and placebo (n = 58). The age of patients included in the study ranged from 18 to 65 years. All patients suffered from urolithiasis with stones up to 10 mm in size. Renalof® was prescribed 1 capsule 3 times a day for 3 months, with monthly clinical, radiological, tomographic and ultrasound monitoring, with the help of which adverse reactions were recorded. The main criterion for assessing the effectiveness of treatment was reduction in the size of the stone or its complete elimination. The reduction in the number of stones was 7.7% in the group of patients taking Renalof® and 0% in the placebo group in the third month, while the elimination of stones was 86.5% in patients in the third month of treatment, which included taking the Renalof® complex. The average number of colics decreased after 3 months, only 0.4 ± 1.3 for the group of patients taking Renalof®. The authors concluded that Renalof® is an effective agent for eliminating or reducing calcium stones in the kidneys and urinary tract without adverse reactions [19-22].

The complex effect of Renalof® is due to the effects of its constituent components and, above all, to the action of the activated extract of the herb Agropyron Repens, the natural diuretic effect of which makes it an ideal substance for the treatment of any urinary tract infections. Moreover, due to its diuretic effect, it can stimulate the passage of kidney stones. Additional therapeutic effects of Wheatgrass are its anti-irritative and anti-inflammatory effects, which helps reduce the likelihood of renal colic during standard lithokinetic therapy. Wheatgrass also has an antimicrobial effect, as it destroys pathogens and prevents their growth. Wheatgrass ensures good regeneration of the epithelium after stone excretion, which has an additional anti-inflammatory effect on the urinary system. Clinical studies have shown that Renalof® has a pronounced anti-inflammatory, antispasmodic and litholytic effect in patients with urolithiasis and ensures painless removal of small stones through the urinary system [16, 17]. The data from the above clinical observations show that a monthly course of using the Renalof® complex leads to normalization of clinical urine analysis parameters [16-19].

Our study represents the first domestic clinical experience of using the Renalof® complex in patients with urolithiasis. Taking into account previous publications, the study design was compiled in such a way as to clarify the action of the complex, taking into account the clinical situations already studied for its use. To achieve the above goal, we divided the patients into 3 groups, which illustrate the vast majority of clinical situations in patients with urolithiasis. Stones up to 5 mm were subjected to conservative lithokinetic therapy and the main group of patients were additionally prescribed Renalof®, which led to a statistically significant increase in the frequency of stone passage from 43.7% to 81.8% of cases, a decrease in the incidence of leukocyturia from 56.3% to 18. 2%, an increase in urine pH from 5.2 to 6.8. Changes in diuresis and visual analogue scale, despite their best indicators in the main group, were statistically unreliable.

The second group of patients consisted of patients whose stones were treated using extracorporeal lithotripsy. The following data was obtained. In the main group of 28 patients, better rates of stone fragment passage and a decrease in leukocyturia rates were achieved. The differences were statistically insignificant in the visual analogue scale and diuresis. As in the first group, changes in urine pH were statistically significant. Thus, the additional use of Renalof improved the effectiveness of extracorporeal lithotripsy and reduced the severity of inflammatory changes in the urine.

In the final part of our study, the clinical effectiveness of the use of the complex in patients after thulium laser lithotripsy was investigated. In this group of patients, the main goal was not to study the frequency of microlith discharge, since their size after laser lithotripsy did not exceed 1 mm. Given the location of the stent, we did not examine the level of leukocyturia and urine pH. However, the frequency of absence of microliths that came off in addition to the stent in the main group was statistically significantly higher than in the control group (84.8% versus 58.3%). Diuresis and visual analogue scale scores were also higher in the main group, however, given the position of the internal stent, we did not consider these changes to be clinically significant.

The additional administration of the Renalof® complex to patients who underwent endourological operations for kidney stones improved their quality of life, slightly increased diuresis, and reduced leukocyturia. At the same time, there was a statistically significant increase in the frequency of absence of kidney stones while taking Renalof® compared to the control group.

Among other clinical advantages of using Renalof®, we can note its safety, since we have not noted any cases of adverse events associated with taking the complex, nor have we identified any deviations in laboratory parameters.

CONCLUSIONS

The use of the Renalof® complex in patients with urolithiasis, including after extracorporeal lithotripsy and in the postoperative period after endoscopic operations on the upper urinary tract, has the following clinical advantages:

- improvement of spontaneous stone passage;

- normalization of urine acidity;

- increased diuresis in patients in the postoperative period;

- reduction in the incidence of leukocyturia in patients in the postoperative period;

- faster removal of residual fragments after endoscopic operations on the upper urinary tract.

LITERATURE

- Turk C. EAU Guidelines on Urolithiasis. EAU Guidelines. Edn. presented at the EAU Annual Congress Amsterdam 2021.

- Menon M, Resnick MI (2007) Urinary lithiasis: etiology, epidemiology and pathogenesis. In: Wein AJ (ed) Campell's Urology vol. 2, 2nd edn. Sounders, Philadelphia.

- Pradère B, Doizi S, Proietti S. Evaluation of Guidelines for Surgical Management of Urolithiasis. J Urol 2021(6). pii: S0022-5347(17)78023-8.

- Srisubat A, Potisat S, Lojanapiwat B, Setthawong V, Laopaiboon M (2009) Extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy (ESWL) versus percutaneous nephrolithotomy (PCNL) or retrograde intrarenal surgery (RIRS) for kidney stones. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 4:CD007044.

- Martov A.G., Ergakov D.V. Application of the Nephradoz complex in the rehabilitation of patients after endourological operations. Urology 2018 (4): 49-55. .

- S. Dhawan, E. O'Olweny. Phyllanthus niruri (stone breaker) herbal therapy for kidney stones; a systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical efficacy, and Google Trends analysis of public interest.. Can J Urol 2021 Apr;27(2):10162-10166.

- Malikh M.A. Methods for identifying residual stones. Bulletin of Surgery of Kazakhstan 2012 (1): 81-82..

- Martov A.G., Ergakov D.V., Guseinov M.A. Initial experience of clinical use of thulium laser lithotripsy in the treatment of urolithiasis. Urology 2021(1):112-120. .

- Bryniarski P, Paradysz A, Zyczkowski M, Kupilas A, Nowakowski K, Bogacki R (2012) Randomized controlled study to analyze the safety and efficacy of percutaneous nephrolithotripsy and retrograde intrarenal surgery in the management of renal stones more than 2 cm in diameter. J Endourol 26:52–57

- Kiremit MC, Guven S, Sarica K, Ozturk A, Buldu I, Kafkasli A, Balasar M, Istanbulluoglu O, Horuz R, Cetinel CA, Kandemir A, Albayrak S (2015) Contemporary management of medium-sized (10–20 mm) renal stones : A Retrospective Multicenter Observational Study. J Endourol 29(7):838– 843. doi:10.1089/end.2014.0698

- Resorlu B, Unsal A, Ziypak T, Diri A, Atis G, Guven S, Sancaktutar AA, Tepeler A, Bozkurt OF, Oztuna D (2013) Comparison of retrograde intrarenal surgery, shockwave lithotripsy, and percutaneous nephrolithotomy for treatment of medium-sized radiolucent renal stones. World J Urol 31(6):1581–1586. doi:10.1007/s00345-012-0991-1

- Sabnis RB, Ganesamoni R, Doshi A, Ganpule AP, Jagtap J, Desai MR (2013) Micropercutaneous nephrolithotomy (microperc) vs retrograde intrarenal surgery for the management of small renal calculi: a randomized controlled trial. BJU Int 112(3):355–361. doi:10.1111/bju.12164

- Armagan A, Karatag T, Buldu I, Tosun M, Basibuyuk I, Istanbulluoglu MO, Tepeler A (2015) Comparison of flexible ureterorenoscopy and micropercutaneous nephrolithotomy in the treatment for moderately sized lower-pole stones. World J Urol 33(11):1827–1831. doi:10.1007/s00345-015-1503-x

- Donaldson JF, Lardas M, Scrimgeour D et al (2015) Systematic review and meta-analysis of the clinical effectiveness of shock wave lithotripsy, retrograde intrarenal surgery, and percutaneous nephrolithotomy for lower-field renal stones. Eur Urol 67:612–616

- De S, Autorino R, Kim FJ et al (2015) Percutaneous nephrolithotomy versus retrograde intrarenal surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Urol 67:125–137

- Beydokthi SS, Sendker J, Brandt S, Hensel A. Traditionally used medicinal plants against uncomplicated urinary tract infections: Hexadecyl coumaric acid ester from the rhizomes of Agropyron repens (L.) P. Beauv. with antiadhesive activity against uropathogenic E. coli. Fitoterapia 2021 Mar;117:22-27. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2016.12.010.

- Popenko E.V. Evaluation of the effectiveness of the drug Renalof in the treatment of patients with urolithiasis. Bulletin of Surgery of Kazakhstan 2012 (1): 78-80. .

- Kristyantoro B, Alif S. Renalof in the management of urinary calculi. Indonesian J of Urol 2012; 19 (2):73 -78.

- Sanchez MK, Villanueva VEu, Vaskez RA. Double-blind RCT of Renalofin in the treatment of renal stone disease. Cuban J. of Herbal Medicine 2012; 31(1):87-100.

- Resorlu B, Unsal A, Gulec H, Oztuna D (2012) A new scoring system for predicting stone-free rate after retrograde intrarenal surgery: the “resorlu-unsal stone score”. Urology 80(3):512–518

- Okhunov Z, Friedlander JI, George AK, Duty BD, Moreira DM, Srinivasan AK, Hillelsohn J, Smith AD, Okeke Z (2013) STONE nephrolithometry: novel surgical classification system for kidney calculi. Urology 81(6):1154–1159

- Martov A.G., Ergakov D.V., Novikov A.B. Modern opportunities to improve the quality of life of patients with internal stents. Urology 2021 (2): 134-140. .

Topics and tags

Urolithiasis disease

Magazine

Journal "Experimental and Clinical Urology" Issue No. 3 for 2020

Comments

To post comments you must log in or register

Clinical symptoms of urolithiasis

Urolithiasis is often asymptomatic, and the patient learns about the presence of deposits by chance from an ultrasound examination of the abdominal cavity.

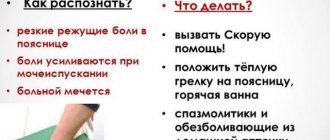

Pain occurs when the flow of urine from the kidney is blocked by deposits located in the renal pelvis or ureter. Colic pain is located in the lumbar region and spreads to the groin, testicle, penis, labia or medial thigh.

Colic pain is located in the lumbar region

Nausea, vomiting and bloating are common. In addition, attacks may be accompanied by difficulty urinating and urge. Patients are restless and cannot find a comfortable position. On physical examination, the kidney is painful on deep palpation, Goldflam's sign is positive.

Symptoms of urolithiasis

At an early stage, when kidney stones do not yet interfere with the flow of urine, the disease may be asymptomatic. As the disease progresses, pain appears in the lumbar region, blood may appear in the urine (hematuria), etc.

Pain due to kidney pathology can be paroxysmal (renal colic) or constant dull. Often radiates to the lateral abdomen and hypochondrium.

There was no direct relationship between the number, size of stones and the severity of symptoms. On the contrary, small stones often manifest themselves as severe pain, and large coral stones often result in dull pain and unpleasant sensations in the lower back.

Laboratory tests

Urinalysis and culture should be performed routinely. In most cases, micro- or macroscopic hematuria is present.

Examination of urine sediment makes it possible to identify crystals and thus indirectly determine the chemical composition of the sediment.

Blood urea and creatinine levels are also measured to rule out kidney failure. A markedly elevated white blood cell count with accompanying fever indicates acute infection.

Urine sediment examination

Visual Research

Imaging studies confirm the clinical diagnosis of urolithiasis. Determining the size of the sediment, its location, and the degree of obstruction of urine flow are important in determining the correct procedure.

- Overview image of the abdominal cavity

. About 90% of urinary tract stones are visible on the overview image. The strongest shadow on the radiograph is produced by calcium oxalate stones, weaker struvite stones and even weaker cystine and gout stones. Uric acid deposits are colorless. - Urography.

Allows you to accurately determine the location of the deposit, and also provides additional information about kidney function and the degree of difficulty in the outflow of urine. In the case of ureteral stones, a photo should be taken after urination to show the obstruction covered by a full bladder. In case of kidney dysfunction caused by impaired urine flow, be sure to take a late photo approximately 2-3 hours after contrast injection. - Ureteropyelography

. It is carried out in the absence of renal function on urography and in the absence of hydronephrosis detected by ultrasound of the abdominal cavity. Additionally, a search is carried out for a non-obscuring stone in the ureter in the survey photograph. - Ultrasound of the abdominal cavity and

. Widely available non-invasive testing. Ultrasound should be performed regularly along with survey photography. Depending on the type of device, it allows you to visualize deposits with a diameter of 4-5 mm. In addition, ultrasound of the bladder and kidneys allows us to assess the degree of stagnation of urine, the condition of the renal parenchyma and the presence of non-obscuring stones. Because ultrasound examinations are harmless, they can be performed on patients with allergies to contrast agents, children and pregnant women.

Abdominal ultrasound

Modern principles of surgical treatment of urolithiasis

Treatment of urolithiasis has two directions: the first is symptomatic treatment (removal or crushing of the stone), the second is the treatment of mainly recurrent stone formation, taking into account its polyetiological factors, complex pathogenesis and variants of the urodynamics of the upper urinary tract. Conservative treatment is carried out for metaphylaxis of recurrent stone formation, with crystalluria and in patients who are stone excretors [11].

Currently, there are many high-tech methods for treating patients with nephrolithiasis: extracorporeal lithotripsy (ESLT), transurethral contact ureterolithotripsy (CTL), flexible ureteronephroscopy with contact lithotripsy, percutaneous and mini-percutaneous nephrolitholapaxy (PNLL), as well as (for urolithiasis complicated by acute pyelonephritis ) laparoscopic uretero- and pyelolithotomy [12–15].

Thus, surgical tactics have recently undergone revolutionary changes. Distinctive features of the current stage of development of methods of surgical treatment of urolithiasis are a reduction in the number of open operations and an increase in the proportion of minimally invasive interventions. According to statistics from urology departments, traditional interventions for urolithiasis account for only 2% of operations. The principles of “fast track surgery” (surgery for accelerated rehabilitation) are also being actively implemented everywhere [16].

The choice of surgical treatment method depends on many factors. If stones are present in the renal pelvis or upper and middle calyx, the procedure of choice is extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy (ESWL), PCLL, or flexible ureteropyelolithotripsy (URL). If stones up to 1.5 cm are detected, the use of ESWL is considered optimal, provided that the stone fragments pass away on their own. If the size of the stone is more than 1.5 cm, then several sessions must be performed when using ESWL, and the risk of ureteral obstruction by the so-called “stone path” increases. At the same time, for stone sizes from 2.0 cm, flexible URL gives good results. This method has a number of advantages: low trauma, low risk of bleeding. In cases of large stones, different approaches using standard or mini-percutaneous LLL are required [17–19].

When the stone is localized in the lower calyx, the use of ESWL may be unsuccessful due to the impossibility of spontaneous passage of residual fragments. With this technique, complete stone removal is achieved in the range from 25 to 85% of interventions. The occurrence of residual urolithiasis is facilitated by certain risk factors, which include: a stone density of more than 1000 HU (Hounsfield Unit), the presence of stones tightly enclosed by the calyx or pelvis, the presence of a long and thin neck of the lower calyx and pathological mobility of the kidney. The most optimal treatment methods for this localization of the stone are endoscopic methods, as well as the use of flexible URLL or PCLL. The disadvantage of these techniques is their invasiveness. However, there are also positive aspects, which include the high efficiency of stone removal and the low risk of developing postoperative complications. The presence of large stones larger than 3.0 cm often requires multi-stage treatment [9, 20].

The introduction of DLT into urological practice has led to a reduction in the number of invasive operations for kidney and ureteral stones, however, it must be taken into account that fragments of crushed stones must pass out of the urinary tract on their own, otherwise another method of stone crushing must be used. If, during a follow-up examination after PCNL, residual stone fragments are detected in a patient with staghorn and large kidney stones, it is preferable to perform transfistula nephroscopy or DLT of residual fragments. At the same time, percutaneous surgery began to occupy an increasing place in the treatment of other, more complex forms of nephrolithiasis; the introduction of this method led to a significant reduction in the number of open operations [21].

In 50% of patients, when a stone is found in the ureter, complicated by acute pyelonephritis or ureteral stricture, congenital or developed after a previous ureterolithotomy, endoscopic treatment is possible in two stages. The first stage includes the elimination of disturbances in the outflow of urine from the kidney and treatment of complications, the second stage is remote crushing, percutaneous or transurethral removal of urinary stones. The two-stage method delays the patient’s recovery, but there is an alternative method - laparoscopic or retroperitoneoscopic ureterolithotomy. It allows you to achieve the main goal - eliminating obstruction of the upper urinary tract, making the operation less traumatic, and reducing the length of hospitalization [4, 22].

Retroperitoneoscopic ureterolithotomy and pyelolithotomy are low-traumatic methods and, along with laparoscopic operations, are used in urological practice [7]. The advantage of the retroperitoneoscopic approach is the presence of anatomical landmarks that facilitate the location of the ureter in the retroperitoneal space, as well as (if certain manual skills are available) stone removal and suturing of the ureteral wall with or without installation of a ureteral stent. With laparoscopic access, the parietal peritoneum is damaged, which leads to the entry of urine, blood and purulent exudate into the abdominal cavity, complicating the course of the postoperative period, as a result of which the patient is subjected to additional manipulations [17].

Over the past 20 years, approaches and technologies for the treatment of urolithiasis have changed, which is associated with the introduction of EBRT, CLT, percutaneous and laparoscopic techniques. Flexible URLP has been widely used, but compared to EBRT, this treatment method is considered invasive. CLT and lithoextraction are indicated when eliminating the “stone path” after ELT sessions [23].

The effectiveness of any treatment method for patients with urolithiasis depends on the rapid and effective restoration of urine outflow from the upper urinary tract, as well as the stage and severity of pyelonephritis. Both of these factors depend on each other, therefore all efforts aimed at relieving pyelonephritis can only be successful if the urodynamics of the upper urinary tract are restored [16].

For transurethral CRT, various lithotripters are used: ultrasound, pneumatic and laser [12], each lithotripter has its own advantages and disadvantages.

After urethral CRT, especially after a long-term stone standing in one place or in case of injury to the ureter during stone crushing, it is better to complete the operation with the installation of a ureteral stent [24].

Currently, puncture nephrostomy as a method of palliative treatment is used in weakened patients with severe concomitant pathologies who need to restore the outflow of urine and relieve pyelonephritis [7, 13].

It should be noted that the size of the stone affects the frequency of disease relapses, the need for multi-stage surgical procedures and the frequency of postoperative complications. According to the American Urological Society clinical guidelines for the surgical treatment of urolithiasis, PCNL is the first-line procedure for the presence of large (more than 2 cm) or staghorn kidney stones. Thus, over 10 years in the United States, the number of PCLLs performed has increased by 47%. Open or laparoscopic surgery is considered the second line of treatment for kidney stones. According to the meta-analysis, the Stone Free rate (“stone-free condition”) in the treatment of staghorn kidney stones during open surgery was 71%, when using PCLL in mono mode - 78%, when using a combination of PCNL and ESWL - 66%, ESWL in mono mode - 54%. In the course of a comparative analysis, the indicator of the total number of operations in the treatment of staghorn kidney stones when performing PCNL was 1.9, with a combination of PCNL and ESWL - 3.3, with ESWL alone - 3.6, with open surgery - 1.4 [17 ].

However, the occurrence of Stone Free also directly depends on the location of the stone. When the stone is localized in the lower calyx, the Stone Free indicator is low as a result of ESWL and is associated with difficulty in passing stones. The use of PCNL does not have a significant effect on the Stone Free rate, regardless of the location of the stone. In a multicenter study comparing the results of ESWL and PCLL for stones larger than 1 cm in size, it was found that the Stone Free rate with PCLL was 3 times higher than with ESWL. When performing PCLL for urolithiasis accompanied by stones less than 1 cm in size, from 1 to 2 cm or more than 2 cm, the Stone Free rate corresponded to 100%, 93% and 86%. With ESWL this figure was estimated at 63%, 23% and 14%, respectively. After 3 months after the operation, with a stone size of 1 to 2 cm, the Stone Free rate after PCNL was 85%, and after ESWL - 33%. Patients from the PCLL group did not require repeated surgical interventions, and with ESWL, repeat sessions were performed in 77% of cases, with 17% of patients undergoing more than 1 ESWL session [5].

The result of the operation also directly depends on the density of the stone, determined by the composition of the stone and expressed in HU. When the stone density is more than 900 HU, determined by computed tomography (CT), the use of ESWL gives an unsatisfactory result, so it is preferable to perform PCNL or retrograde transurethral ureterolithotripsy. The presence of compounds such as cystine, calcium oxalate monohydrate or brushite in the stone makes it insufficiently sensitive to ESWL. CT results also determine the distance from the skin to the stone, since this is an important factor in the effectiveness of ESWL. If this indicator is less than 9 cm, then the effectiveness of ESWL is 79%; increasing the distance by more than 9 cm reduces the effectiveness to 57%. At the same time, the effectiveness of PCNL does not depend on the patient’s body mass index and the distance from the skin to the stone. When assessing quality of life using standard questionnaires, the survey results were better after PCLL [7].

Treatment of urolithiasis

In case of an attack of renal colic, treatment depends on the following factors:

- the size of the deposit and the likelihood of its spontaneous removal,

- concomitant diseases (diabetes mellitus, solitary kidney),

- complications of urolithiasis (impaired urine outflow, urinary tract infection).

Outpatient treatment is provided to patients in good general condition with stones less than 5 mm in diameter. It is recommended to use painkillers and antispasmodics, drink plenty of fluids and be physically active.

To determine the degree of displacement of deposits in the urinary tract, films of the abdominal cavity are taken every 7-14 days. Deposits with a diameter of more than 5-10 mm are rarely removed spontaneously; such patients may require hospitalization and surgical intervention.

Indications for hospitalization are:

- significant difficulty in the outflow of urine due to a stone with a diameter of more than 10 mm,

- high temperature (more than 38 ° C),

- persistent renal colic, which does not go away after taking painkillers and diastolic drugs.

- severe vomiting with dehydration,

- colic in patients with one kidney,

- concomitant diabetes, especially unregulated type 2,

- pregnancy.

Inpatients should receive intensive hydration, especially if both diabetes mellitus and a urinary tract infection are present. Broad-spectrum antibiotics are administered parenterally.

Parenteral administration of antibiotics

Immediate drainage of urine is required if there is a stone blocking drainage from the kidney and signs of a urinary tract infection. A ureteral catheter or Double J catheter may be inserted into the kidney for this purpose, as long as this maneuver does not create a percutaneous renal fistula. In these cases, the main treatment is postponed until the inflammation is relieved.

Diagnosis of urolithiasis

In the urology clinic of the First Moscow State Medical University, if urolithiasis is suspected, a detailed examination is carried out. It allows not only to identify the presence and composition of the stone, but also to establish the cause of its formation.

Metabolic processes, the state of blood and urine, hormonal levels must be checked, possible diseases predisposing to urolithiasis, etc. are identified.

The first step in diagnosing urolithiasis is ultrasound. It can be used to identify stones larger than 5 mm or to suspect stones of a smaller size.

The exact size of the stones, their location, density and composition are determined by multislice computed tomography (MSCT), which has almost 100% sensitivity. Including the so-called X-ray negative stones consisting of uric acid.

Surgical treatment of urolithiasis

The discovery and use of ESWL (extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy) in the treatment of urolithiasis has revolutionized the treatment of this disease. The combination of ESWL and endourological methods almost completely eliminated the need for surgical treatment.

Approximately 50% of patients with symptomatic urolithiasis require surgery. In other cases, the stone is released spontaneously.

- ESWL ( extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy )

– extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy. Currently, it is the most common method of treating urolithiasis. Its effectiveness is estimated at 50-95% depending on the type of device, size and location of the stones. Currently, devices are used that generate electromagnetic, electrohydraulic or piezoelectric waves. The procedure is usually performed on an outpatient basis without anesthesia, and if you have a low pain threshold, painkillers are usually sufficient. Patients with deposits of 1.5-2 cm in the calyx or renal pelvis, as well as stones in the ureter, are suitable for treatment. Contraindications to ESWL include pregnancy, urinary tract infection, anatomical obstruction below the sediment and bleeding disorders. - URS (ureterorenoscopy)

is a method in which urine deposits are visually removed from the ureter using a ureterorenoscope. The deposits in the ureter are crushed and then removed with forceps or suitable baskets. The effectiveness of treatment is estimated at 60-95%. This treatment is suitable for patients with lower ureterolithiasis. Contraindications are the same as for ESWL. The most serious complication is perforation of the ureteral wall. - PCNL (percutaneous nephrolithotripsy)

is a method that allows you to remove urine deposits located in the renal collecting system and the upper ureter through a renal fistula formed in the lumbar region. The effectiveness of this treatment method reaches 90%. Most often, patients with kidney stones larger than 2 cm, as well as complete or partial metastases, are suitable candidates.

Extracorporeal Shock Wave Lithotripsy

Hard deposits that are refractory to ESWL are also an indication for PCNL. Contraindications are anatomical defects of the kidneys and skeletal system that prevent proper puncture, as well as urogenital tuberculosis. The most common complications include bleeding, damage to organs adjacent to the kidney, perirenal hematoma, and infiltration of urine into the retroperitoneal space.

In clinical practice, it is often necessary to repeat the procedure or use a second type of adjuvant treatment, such as ESWL.

Surgical treatment in centers with appropriate equipment is extremely rare. It is performed for anatomical abnormalities of the urinary system and extensive hypertensive urolithiasis, especially bilateral. In recent years, laparoscopy has been increasingly used in urological procedures, including the treatment of urolithiasis.

A separate problem is urolithiasis, which occurs mainly in men over 70 years of age. Most likely, the reason is that the kidney stones are not removed due to obstruction of urine flow due to bladder obstruction.

The main reason for the formation and growth of stones is residual urine in the bladder and diverticula after urination. Stones in the bladder can appear due to the presence of foreign bodies, such as pieces of thread after bladder surgery, necrotic tumor tissue. Infection of the urinary tract with urea-positive bacteria contributes to the formation of deposits in the bladder.

The most common symptoms include pain, hematuria, and urinary problems. The pain is located above the symphysis pubis in the perineum, vulva, scrotum and glans. Worse at the end of urination when the bladder contracts over the stone. Calms down in a lying position. Moderate hematuria occurs mainly after exercise. Patients report pollakiuria, intermittent stream, and intermittent urinary retention.

The diagnosis of urolithiasis is based on a correctly collected medical history, examination of the abdominal organs and ultrasound. Final confirmation is cystoscopy.

Depending on the condition of the bladder, treatment is carried out using transurethral lithotripsy or surgery. An important factor in preventing the recurrence of bladder stones is removing the bladder obstruction.

Diagnosis of urolithiasis (UCD)

When diagnosing urolithiasis (UCD), depending on the causes of formation and composition, stones are divided into three types of stone formation:

- calcium - up to 70% of patients

- metabolic (uric acid) - up to 12%

- infected - up to 15%

- patients with cystine stones - up to 2 - 3%

Determining the mineral composition of stones is necessary to prevent recurrent stone formation. Patients with recurrent stone formation due to urolithiasis (UCD), after identifying the causes of stone formation, are prescribed a set of measures (metaphylaxis) to prevent recurrent stone formation.

Depending on the location of the stone, a patient with urolithiasis (UCD) may complain of different symptoms, but the main ones for this disease are:

- paroxysmal pain

- blood in the urine

- deterioration in general health

With a kidney stone, pain often occurs during physical activity, and other diseases of the genitourinary tract may worsen in patients. If the stone is in the bladder, then the patient with urolithiasis (UKD) is bothered by frequent painful urination, as well as pain that appears when moving.

When a stone is located in the ureters, a patient with urolithiasis (UKD) experiences a frequent urge to urinate, pain moving from the lower back to the inner thigh, groin and lower abdomen.

If a stone blocks the lumen of the ureter and urine accumulates in the kidney, renal colic begins. A patient with urolithiasis (UKD) experiences acute pain in the lower back, spreading to the abdomen. The colic continues until the stone changes its position or leaves the ureter.

Multiple calculi (stones) in the kidney due to urolithiasis, located in the pelvis and at the entrance to the ureter.

Sources

- Tizelius H.G. et al.: Recommendations for urolithiasis, 2000.

- Preminger GM: Treatment of urolithiasis: pathogenesis and diagnosis, 1995.

- Dretler S.P. Treatment of ureteral stones, 1995.

- Macfarlane MT: Urolithiasis, 1997.

- Drach G.V.: Urinary lithiasis. Campbell Urology, 1992.

ONLINE REGISTRATION at the DIANA clinic

You can sign up by calling the toll-free phone number 8-800-707-15-60 or filling out the contact form. In this case, we will contact you ourselves.

If you find an error, please select a piece of text and press Ctrl+Enter