Hidden threat

But why don’t people turn to doctors until the stone completely fills the kidney space? The fact is that coral deposits, despite their size, do not cause pain or significant discomfort. Therefore, patients are unaware of their existence until the situation becomes critical. The second reason for untimely treatment is the formation of stones in the damaged kidneys.

Coral deposits are formed against the background of:

- existing disorders of phosphorus-calcium metabolism;

- albuminuria - high concentration of protein in the urine;

- genitourinary infections;

- pyelonephritis;

- genetic kidney disorders and anomalies;

- pathologies of blood vessels of the urinary system.

Therefore, patients accustomed to kidney problems attribute minor manifestations of the disease to existing diseases. The growth of huge stones leads to the development of infection, disruption of the outflow of urine and death of organ structures. This brings the patient to the clinic, where huge stones are discovered on ultrasound.

Diagnosis of coral kidney stones

The diagnosis of coral nephrolithiasis is based on general signs and additional research data. Therefore, staghorn stones can be detected during an examination, such as an x-ray of the urinary tract or an ultrasound examination.

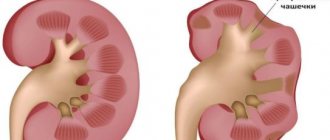

Thanks to ultrasound and x-ray during diagnosis, in 100% of cases it is possible to determine the size and contours of the kidney, the projection shadow, the size of the coral stone, and also to determine the expansion of the pyelocaliceal system. Excretory urography makes it possible to more accurately assess the functional activity of the kidneys, identifying the expansion of the pyelocaliceal system.

To identify chronic renal failure at different stages, the urologist:

- studies the lifestyle of patients;

- collects information about their living conditions preceding the disease coral nephrolithiasis;

- analyzes the current clinical picture of the disease;

- evaluates data and readings received from the laboratory.

Thanks to the constant improvement of urologists, the development of new scientific methods and a change in the fleet of diagnostic equipment, the number of patients suffering from coral nephrolithiasis in the terminal stage of chronic renal failure is steadily decreasing.

In chronic renal failure in patients with coral stones, plasma proteins are detected - albumin, transferrin, acid glycoprotein. Immunoglobulins, beta-lipoproteins and a2-macroglobulins can also get into the urine.

This indicates a violation of the integrity of the glomerular basement membranes, which usually does not allow plasma proteins to enter the urine. Changes in the functional activity of the kidneys lead to disruption of carbohydrate metabolism due to an increase in the proportion of insulin in the blood.

Symptoms of coral lithiasis

There are several stages of development of coral stones (coral lithiasis):

- Hidden

- there are no manifestations of the disease. There may be minor pain in the lower back. - Initial

- periodic increases in temperature and pressure, thirst, weakness, and minor swelling of the face are added. - Clinical

– constant pain in the lower back, loss of strength, and urinary problems appear. There are traces of blood and small pebbles in the urine - broken fragments of coral. - Hyperazotemic

- renal failure increases, edema appears, temperature rises, and blood pressure surges are observed. When pyelonephritis occurs, pus is detected in the urine, and leukocytes in the blood increase and ESR accelerates. The expansion of the pelvis leads to hydronephrosis - the accumulation of urine inside the kidney. Acute urinary retention occurs, requiring urgent hospitalization.

Percutaneous nephrolithotomy in the treatment of coral kidney stones K3-K4

Merinov D.S., Artemov A.V., Epishov V.A., Arustamov L.D., Gurbanov Sh.Sh., Fatikhov R.R.

The development of endoscopic urology and the improvement of endoscopic instrumentation has led to a significant decrease (10–15 times) in the role of traditional open surgical interventions in patients suffering from coral nephrolithiasis [1]. The recommendations of the European Association of Urology state that open stone removal surgery is used as the exclusive intervention for the removal of very large staghorn stones. In developed countries, open surgery for urolithiasis is currently performed in approximately 1.5% of patients [2].

Currently, according to most domestic and foreign authors, the effectiveness of percutaneous nephrolithotomy (PNL) in patients with coral kidney stones varies from 55 to 98% [2-4]. It should be emphasized that some studies have noted the following relationship: the larger the size of the stone and the more complex its configuration, the more often repeated and additional surgical interventions are required in this category of patients [5]. In an article by the CROES PCNL Study group, based on an analysis of the results of treatment of a large group of patients, it was concluded that the effectiveness of PCNL for complete staghorn kidney stones when performing 1-2 approaches does not exceed 50% [6]. However, other studies have published results with an effectiveness rate of 70-83% [3,4]. When performing multi-PNL, some authors indicate results at the level of 8389%, noting the presence of a direct relationship between the amount of bleeding, purulent-inflammatory complications and the number of accesses performed [6-9].

Thus, the question of studying the effectiveness and feasibility of performing two or more percutaneous approaches to achieve optimal results in patients with complete staghorn kidney stones remains extremely relevant. In this article, we summarized our experience of performing PCNL in patients suffering from complete staghorn kidney stones.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Over the past 6 years at the Research Institute of Urology and Interventional Radiology named after. ON THE. Lopatkin, we treated 938 patients who were diagnosed with stage K3-K4 coral kidney stones according to the classification developed at the Research Institute of Urology in 1983 [10]. The main characteristics of the patients are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Basic characteristics of patients included in the study (n=938)

| Sign | Meaning |

| Age, years M (25;75%) | 57 (36; 69) |

| Presence of concomitant diseases, % | 594 (63,3%) |

| Stone size, mm M (25;75%) | 58 (42;78) |

| Stone volume, mm3 M (25;75%) | 693,9 (381,3; 1223,4) |

| Stage K3 coral stone, % | 634 (67,6%) |

| Coral stone K4 stage, % | 304 (32,4%) |

| Recurrent stones, % | 397 (42,3%) |

| Presence of bacteriuria, % | 627 (66,8%) |

| Presence of heart rate expansion, % | 482 (51,4%) |

| Deficiency of renal secretory function on the side of the operation, % | 43 (32; 66) |

All patients were examined in the preoperative period according to the generally accepted algorithm for this category of patients. The median age was 57 (36; 69) years. 63.3% of patients in this group had concomitant diseases. The median stone size was 58 (42; 78) mm and the median stone volume was 694 (381; 1223) mm3. The maximum size and volume of the stone was calculated based on the results of computed tomography performed in the native phase. Based on the classification of coral nephrolithiasis, we observed 634 (67.6%) patients who were diagnosed with stage K3 stones and 304 (32.4%) with stage K4 coral stones. Recurrent nephrolithiasis was detected in 397 (42.3%) patients, while the vast majority of these patients, namely 331 (83.4%), had a history of open surgical interventions for urolithiasis and its complications. In 627 (66.8%) patients, according to bacteriological examination of urine, an increase in microflora was detected, which required antibacterial therapy at the preoperative stage. According to ultrasound examination of the kidneys, 482 (51.4%) patients included in the study had signs of impaired urodynamics of the upper urinary tract, however, it should be noted that in the vast majority (87.3%) of patients only minimal dilatation of the calyces was detected. According to dynamic nephroscintigraphy, all patients with stage 3-4 coral stones had disturbances in the secretory and excretory functions of the kidney. At the same time, the median deficiency of secretory function was 43% (32; 66).

All PCNL operations were performed under endotracheal anesthesia with the patient in the prone position. Access to the renal collecting system was carried out under combined ultrasound and fluoroscopic control with preliminary installation of a ureteral catheter. Puncture approaches to the stone and their number were planned at the preoperative stage. When planning to perform multi-PNL, several accesses to the pyelocaliceal system were sequentially created at the very beginning of the surgical intervention, leaving wire strings. Bougienage of the main puncture channel was performed using telescopic Alken until 24-26 Ch. In a number of observations, we used a mini-nephroscope to create additional access, while the puncture tract was bougiened using specially designed bougies for this instrument to 14.5-15.5 Ch. To disintegrate stones, we used an ultrasonic lithotripter “LithoClast Master” with simultaneous lapaxy of fragments. The surgical intervention was completed with the installation of nephrostomy drainage No. 10-20 Ch. In the postoperative period, ultrasound examination, survey urography and, if indicated, computed tomography were performed to determine residual fragments. Residual fragments larger than 5 mm were considered clinically significant.

RESULTS

At the clinic of the Research Institute of Urology and Interventional Radiology named after. ON THE. Lopatkina in the period from 2010 to 2015. 2,456 percutaneous nephrolithotomies were performed in patients for urolithiasis. In 938 patients, stage K3-K4 coral kidney stones were detected at the preoperative stage. Of these, 451 (48.2%) surgical interventions were performed using the multi-PNL technique (Fig. 1). Positive dynamics were noted, indicating an increase in the number of treated patients with stage K3K4 coral kidney stones and the number of multi-PNL performed in this category of patients.

Rice. 1. Dynamics of multi-PNL in patients with stage K3-K4 stones

Table 2 presents data on the number of surgical approaches performed in patients with stage K3-K4 staghorn stones. Thus, one access was performed in 487 patients, which amounted to 51.8%. PCNL from two approaches was performed in 371 (39.6%) patients. 64 (6.9%) and 14 (1.5%) patients required three and four approaches during surgery. In two patients, PCNL was performed using five puncture approaches.

Table 2. Distribution of patients depending on the number of puncture approaches (n=938)

| Number of accesses | Absolute number (n) | Relative number (%) | ||

| 1 access | 487 | 51,8 | ||

| 2 accesses | 371 | 451 | 39,6 | 48,2 |

| 3 accesses | 64 | 6,9 | ||

| 4 accesses | 14 | 1,5 | ||

| 5 accesses | 2 | 0,2 | ||

It should be noted that in the vast majority of observations, namely in 78% of observations (352 out of 451), to create additional access to the stone, we used a set for mini-percutaneous surgery with tubes 14.5 Ch and 15.5 Ch.

The main results and effectiveness indicators of surgical interventions in the form of mono- and multi-PNL are shown in Table 3.

Table 3. Efficacy of mono and multi-PNL in patients with stage K3-K4 staghorn stones (n=938)

| Efficiency, % | Mono-PNL (n=487) | Multi-PNL (n=451) | PCNL from 2 approaches (n=371) | PCNL from 3 approaches (n=64) | PCNL from 4 approaches (n=14) | PCNL from 5 approaches (n=2) |

| Efficiency, % | 53,6 | 83,8* | 79,6 | 87,7 | 89,1 | 50 |

| Operation duration, min. | 74,2±29,9 | 92,7±34,5* | 85,7±26,9 | 116,6±28,7 | 144,0±12,2 | 177,7±15,3 |

| Fluoroscopy time, sec. | 126,6 (108;201) | 385,1(296;772)* | 184,3 (154;306) | 346,7 (311;617) | 501,3 (456;703) | 708 (648;812) |

| Bed days after surgery, days. | 6,6 (5,4;8,7) | 10,2 (8,6;12,3)* | 8,3 (6,9;11,6) | 9,7 (8,3;12,6) | 10,1 (8,3;13,5) | 16,5 (10;23) |

| Number of complications, n, (%) | 99 (20,3) | 115 (25,5)* | 94 (25,3) | 14 (21,9) | 5 (35,7) | 2 (100) |

Note: * p≤0.05

The rate of complete stone clearance in our study varied significantly. The effectiveness of mono-PNL in patients with stage K3-K4 staghorn stones was 53.6% and when performing multi-PNL – 83.8% (p≤0.05).

The average duration of the operation in the overall group was 86.2±38.9 minutes and increased depending on the number of puncture approaches performed: 74.2±29.9 minutes when performing one access, 85.7±26.9 minutes when performing two accesses, 116.6±28.7 minutes – when performing three accesses, 144.0±12.2 minutes – when performing 4 accesses. The duration of multi-PNL with 5 approaches was 177.7±15.3 minutes, respectively.

The median fluoroscopy time in the overall group was 266 (184;584) seconds. When performing PCNL from a single access, the median fluoroscopy time was 126.6 (108;201) seconds, with multi-PNL 385.1 (296;772) seconds (≤0.05), and differed significantly depending on the number of accesses created and the diameter used tool. It took 184.3 (154;306) seconds to create 2 accesses, 346.7 (311;617) seconds for 3 accesses, 501.3 (456;703) seconds for 4 accesses and 708 (648 ;812) seconds when performing PNL from 5 accesses.

One of the indicators of effectiveness and safety in the early postoperative period is the length of the patient's stay in the hospital after surgery. Thus, the median bed-day for PCNL from one access in our study was 6.6 (5.4; 8.7) days. In the multi-PNL group, this indicator was 10.2 (8.6;12.3) days (p≤0.05). At the same time, with an increase in the number of accesses, there was a tendency towards an increase in the duration of hospitalization (on average from 8.3 to 16.5 days).

We noted complications in the intraoperative and early postoperative period in 99 (20.3%) patients when performing one access during surgery and in 115 (25.5%) patients when performing several approaches to the stone (p≤0.05). In the group of patients in whom the operation was performed using two approaches, the overall complication rate was 25.3% (94 patients). When creating 3 and 4 approaches, complications developed in 14 (21.9%) and 5 (35.7%) patients.

The nature of complications in patients with stage K3-K4 staghorn kidney stones is clearly presented in Table 4.

Table 4. Nature of complications during PCNL in patients with stage K3-K4 staghorn kidney stones (n=938)

| Efficiency, % | Mono-PNL (n=487) | Multi-PNL (n=451) | PCNL from 2 approaches (n=371) | PCNL from 3 approaches (n=64) | PCNL from 4 approaches (n=14) | PCNL from 5 approaches (n=2) |

| Attack of pyelonephritis, n (%) | 92 (18,9) | 93 (20,6) | 75 (20,2) | 14 (21,9) | 3 (21,3) | 1 (50) |

| Bleeding, n (%) | 46 (9,5) | 54 (11,9) | 45 (12,2) | 6 (9,4) | 2 (14,2) | 1 (50) |

| Exacerbation of chronic renal failure, n (%) | 0 | 3 (0,7) | 0 | 1 (1,6) | 1 (7,1) | 1 (50) |

| Pleural injury, n (%) | 1 (0,2) | 5 (1,1) | 2 (0,5) | 2 (3,2) | 1 (7,1) | 0 |

Note: p≥0.05

The most common complication in the postoperative period was exacerbation of chronic pyelonephritis of varying severity, which was noted in 92 (18.9%) and 93 (20.6%) patients after mono-PNL and multi-PNL surgery. We did not notice an increase in the number of purulent-septic complications when performing two or more approaches in this category of patients (p≥0.05).

Bleeding during and in the early postoperative period in our study was observed in 46 (9.5%) patients in whom the operation was performed through one access and in 54 (11.9%) patients who required stone removal using two or more accesses into the pyelocaliceal system (p≥0.05).

We observed complications from the chest organs in the form of pneumonia and urothorax in 1 (0.2%) patient after stone removal from one access and in 5 (1.1%) patients who required the creation of several percutaneous tracts. We did not note any injuries to the abdominal organs in any patient.

In order to relieve complications of various natures, we performed additional interventions and procedures, the main ones of which are presented in Table 5.

Table 5. Interventions and procedures aimed at relieving complications (n=938)

| Interventions and procedures | Mono-PNL (n=487) | Multi-PNL (n=451) | PCNL from 2 approaches (n=371) | PCNL from 3 approaches (n=64) | PCNL from 4 approaches (n=14) | PCNL from 5 approaches (n=2) |

| Kidney revision, n (%) | 0 | 1 (0,2) | 0 | 1 (1,6) | 0 | 0 |

| Nephrectomy, n (%) | 0 | 1 (0,2) | 0 | 1 (1,6) | 0 | 0 |

| Embolization, n (%) | 1 (0,2) | 3 (0,6) | 2 (0,5) | 1 (1,6) | 0 | 0 |

| Blood transfusion, n (%) | 25 (5,1) | 26 (5,8) | 19 (5,1) | 5 (7,8) | 1 (7,1) | 1 (50) |

| Efferent methods of detoxification, n (%) | 88 (18,1) | 88 (19,5) | 70 (18,8) | 14 (21,8) | 3 (21,3) | 1 (50) |

| Hemodialysis, n (%) | 0 | 1 (0,2) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (50) |

In our study, emergency revision of the kidney and its removal was required in only one patient, in whom, on the third day after multi-percutaneous nephrolithotomy, repeated bleeding was noted and, due to the anatomical features of the blood supply to the kidney, it was not possible to stop this complication using other methods available in the clinic , including endovascular.

In the early postoperative period, blood transfusions were required in 25 (5.1%) and 26 (5.8%) patients after mono- and multi-PCNL, respectively (p≥0.05).

To relieve inflammatory complications, 88 (18.1%) and 88 (19.5%) patients from the mono- and multi-PNL groups, respectively, underwent extracorporeal detoxification methods in the form of laser blood irradiation and plasmapheresis (p≥0.05).

Due to the development of acute renal failure in the early postoperative period after stone removal from 5 approaches, 1 patient required hemodialysis.

DISCUSSION

Over the past few years in Russia there has been an increase in the number of centers that perform high-tech endoscopic interventions in patients with coral nephrolithiasis, which leads to a decrease in the proportion of open operations. It should be noted that in the period from 2010 to 2015. We have noted a significant increase in the number of patients with complex forms of nephrolithiasis from various regions of the Russian Federation at the Research Institute of Urology and Interventional Radiology named after. ON THE. Lopatkina. Thus, over the past 6 years, our institute has noted an increase in the number of patients with stage K3-K4 coral stones by 359% and, accordingly, an increase in the number of multipercutaneous interventions from 10 to 167, i.e. by 1670%.

Analyzing our own results of percutaneous interventions, we noted an increase in the percentage of complete removal of coral stones when creating two or more approaches, namely from 53.6% to 83.8%. In other works of domestic and foreign colleagues, this indicator is comparable to ours [11-14]. It is also obvious that with an increase in the number of accesses created, both the time of surgical intervention and the time of fluoroscopy increase.

When analyzing complications in the intra- and early postoperative periods in groups of patients who underwent PCNL from single and multiple approaches, we noted an increase in the number of complications, namely from 20.3% to 25.5%. The most common complication was exacerbation of chronic pyelonephritis. It is known that one of the reasons for the development of purulent-septic complications is the adequacy of kidney drainage after stone removal. When analyzing the literature data, we encountered different approaches to methods of renal drainage at the stage of completion of PCNL. Thus, some authors, when performing multi-PNL, indicate the need to drain the kidney with one nephrostomy without installing additional nephrostomies and calicostomies in cases where there are no signs of bleeding from additional approaches [13]. In other studies, the authors complete the surgical intervention with the installation of several nephrostomes and calicostomies, usually equal to the number of accesses created to the stone [14]. In our work, when creating several accesses to the pyelocaliceal system, we completed the surgical intervention by installing several nephrostomes or calicostomes. When using a mininephroscope through additional puncture approaches at the stage of deciding whether to install a calicostomy, we were guided by the degree of bacteriuria in the preoperative period, the severity of bleeding and the intensity of urine staining with blood along the main nephrostomy at the completion of the operation. In cases where we had to perform bougienage or other corrective interventions on the necks of the calyces, we always installed several nephrostomy drains, since, in our opinion, during the removal of a complete staghorn stone there are several interrelated factors that influence the development of complications in the postoperative period. These factors include: the size and chemical composition of the stone, the presence and degree of bacteriuria, the severity of the deficiency of the secretory function of the kidney, the duration of the surgical intervention, the accuracy of the surgeon, the degree of intraoperative blood loss and, of course, the anatomical features of the collecting system.

To relieve infectious complications, complex antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, infusion, and symptomatic therapy was carried out. In this case, the choice of antibacterial therapy was based on the results of a bacteriological analysis of urine with determination of sensitivity to antibacterial drugs taken at the prehospital stage. However, along with complex therapy, 18.1% of patients from the mono-PNL group and 19.5% of patients from the multi-PNL group required additional detoxification methods in the early postoperative period. At the same time, we did not note a statistically significant difference in the number of efferent detoxification methods performed (laser blood irradiation, hemofiltration) between subgroups of patients depending on the number of accesses created (p≥0.05).

One of the most serious complications in percutaneous surgery is bleeding, both during surgery and in the early postoperative period. The literature is ambivalent about the incidence of bleeding depending on the number of accesses created. Thus, some authors indicate that the number of accesses does not affect the percentage of hemorrhagic complications [13,15], others prove that the percentage of bleeding and the need for blood transfusions increase significantly when performing multi-PNL [16]. In our work, the percentage of hemorrhagic complications was 9.5% when performing mono-PNL and 11.9% when performing multi-PNL (p≥0.05). We also did not obtain a statistically significant difference between the groups of patients in such indicators as the need for kidney revision (p≥0.05), emergency nephrectomy (p≥0.05) and embolization of renal vessels (p≥0.05). However, in this work, we did not conduct a comparative analysis between subgroups of patients for whom additional access was created using a mininephroscope.

Also one of the serious complications is injury to the parietal pleura and lung tissue. In our study, we observed this complication in one (0.2%) patient from the mono-PNL group and in 5 (1.1%) patients from the multi-PNL group. Moreover, all these complications were noted when performing access to the pyelocaliceal system through the upper group of cups. We emphasize that timely diagnosis of this complication and timely drainage of the pleural cavity allows one to avoid purulent-inflammatory complications from the respiratory tract.

CONCLUSIONS

1. Percutaneous nephrolithotomy with the creation of several accesses to the renal collecting system can significantly increase the effectiveness of this method of treatment in patients with coral nephrolithiasis at stages K3-K4. The clinical effectiveness of mono-PNL and multi-PNL is 53.6% and 83.8%, respectively.

2. With an increase in the number of accesses created during surgery, there is an increase in the time of the operation itself, the radiation exposure on the patient and on the medical personnel working in the X-ray operating room increases significantly, the total number of complications increases, which in turn leads to a longer the period of the patient's hospitalization.

3. Creation of additional access to the pyelocaliceal system leads to an increase in the total number of intra- and postoperative complications, however, we did not note statistically significant differences between the mono-PNL and multi-PNL groups in such serious complications as: attack of pyelonephritis, intra- and early postoperative bleeding , injury to the pleural cavity and exacerbation of chronic renal failure. The optimal number of accesses for one surgical intervention should not exceed three.

LITERATURE

1. Merinov D.S., Pavlov D.A., Gurbanov Sh.Sh., Fatikhov R.R., Epishov V.A., Artemov A.V., Shvangiradze I.A. Our 5-year experience in performing percutaneous nephrolithotomy in patients with large and staghorn kidney stones. Experimental and clinical urology. 2014;(2):54-60

2. Turk C., Knoll T., Petrik A., Sarica K., Straub M., Seitz C. Guidelines of urolithiasis. European Urological Association, 2014. URL: https://uroweb.org/guideline/urolithiasis/#3.

3. Akman T, Sari E, Binbay M, Yuruk E, Tepeler A, Kaba M, Muslumanoglu AY, Tefekli A. Comparison of outcomes after percutaneous nephrolithotomy of staghorn calculi in those with single and multiple accesses. J Endourol 2010;24(6):955-960.

4. Wang Y, Hou Y, Jiang F, Wang Y, Wang C. Percutaneous nephrolithotomy for staghorn stones in patients with solitary kidney in prone position or in completely supine position: a single-center experience. Int Braz J Urol 2012; 38(6):788-794.

5. Cho HJ, Lee JY, Kim SW, Hwang TK, Hong SH. Percutaneous nephrolithotomy for complex renal calculi: is multi-tract approach ok? Can J Urol 2012;19(4):6360-6365.

6.Opondo D, Tefekli A, Esen T, Labate G, Sangam K, De Lisa A, Shah H, de la Rosette J. Impact of case volumes on the outcomes of percutaneous nephrolithotomy. CROES PCNL study group. Eur Urol 2012;62(6):1181-1187.

7.Aron M, Yadav R, Goel R, Kolla SB, Gautam G, Hemal AK, Gupta NP. Multi-tract percutaneous nephrolithotomy for large complete staghorn calculi. Urol Int 2005;75(4):327-32.

8. Singla M, Srivastava A, Kapoor R, Gupta N, Ansari MS, Dubey D, Kumar A. Aggressive approach to staghorn calculi-safety and efficacy of multiple tracts percutaneous nephrolithotomy. Urology 2008;71(6):1039-1042.

9. El-Hahas AR, Shoker AA, El-Assmy AM, Mohsen T, Shoma AM, Eraky I, El-Kenawy MR. Postpercutaneous nephrolithotomy extensive hemorrhage: a study of risk factors. J Urol 2007;177:576-574.

10. Akulin S.M. Complications of surgical interventions in the treatment of patients with coral nephrolithiasis (treatment and prevention): Abstract of thesis. dis. ...cand. honey. Sci. Moscow, 2010. 29 p.

11. Mazurenko D.A., Zhivov A.V., Bernikov E.V., Kadyrov Z.A., Yagudaev D.M., Yengay V.A., Comparison of laser (ho:yag) and pneumatic lithotripsy for percutaneous nephrolitomy of large and high-density coral kidney stones. Laser Medicine 2015;19(2):27-29

12. De la Rosette J, Assimos D, Desai M, Gutierrez J, Lingeman J, Scarpa R, Tefekli A. clinical research office of the endourological society percutaneous nephrolithotomy Global study: indications, complications, and outcomes in 5803 patients . J Endourol 2011;25(1):11-17.

13. Mazurenko D.A., Zhivov A.V., Bernikov E.V., Kadyrov Z.A., Abdullin I.I., Nersesyan L.A. “Fast-track” strategy for postoperative management of patients after percutaneous nephrolithotomy . Experimental and Clinical Urology 2016;(1):36-42.

14. Abdelhafez MF, Amend B, Bedke J, Kruck S, Nagele U, Stenzl A, Schilling D. Minimally invasive percutaneous nephrolithotomy: a comparative study of the management of small and large renal stones. Urology 2013;81(2):241-245.

15. De Cogáin MR, Krambeck AE. Advances in tubeless percutaneous nephrolithotomy and patient selection: an update. Curr Urol Rep 201314(2):130–137.

16. Ganpule AP, Desai M. Management of the staghorn calculus: multiple-tract versus single-tract percutaneous nephrolithotomy. Curr Opin Urol 2008;18(2):220-223.

Journal "Experimental and Clinical Urology" Issue No. 3 for 2016

Topics and tags

Urolithiasis disease

Magazine

Journal "Experimental and Clinical Urology" Issue No. 3 for 2016

Comments

To post comments you must log in or register

Treatment of coral stones

Stones are removed surgically using contact lithotripsy. Under the control of a video camera, an instrument is inserted into the kidney cavity, which crushes deposits using a laser or ultrasound. The fragments are removed, and small fragments and sand come out with a stream of urine through the installed catheter. Some stones can be crushed using a non-contact method when exposed to shock waves through the skin.

To eliminate the infection, antibiotics and anti-inflammatory drugs are prescribed. After treatment, a diet is recommended to prevent the deposition of new stones. Dishes are prepared without salt. Excluded from the menu:

- salted, smoked, spicy dishes, cheeses, canned food;

- legumes, chocolate, cocoa, alcohol, coffee;

- mushrooms, sorrel and dishes made from them;

- rich broths;

- refractory fats.

Eggs, cottage cheese, white bread, pasta, rice are limited. Steamed dishes, low-fat broth, boiled vegetables, fruits, and cereals are allowed. Vegetable decoctions and herbal teas are useful.

4.Treatment

Today, many approaches, methods, and specific techniques for the treatment of coral nephrolithiasis have been developed and are successfully used. With some variants of the chemical composition of stones, for example, with a predominance of urates, i.e. uric acid salts - there is a certain chance of getting by with conservative treatment, gradually “dissolving” the calculus. In any case, for the treatment and/or prevention of infectious and inflammatory exacerbations, specially selected (based on the results of bacteriological analysis) antibiotics are prescribed. However, a much more effective and promising direction is minimally and minimally invasive surgery (for example, percutaneous puncture nephrolithotripsy, external shock wave lithotripsy, percutaneous percutaneous nephrolithotripsy, etc.), aimed at crushing and removing stones from the kidney. General principles that are followed to the last possible extent are the avoidance of open abdominal intervention, the choice of organ-preserving methods and the maximum stabilization of renal functions in the postoperative period. Of course, advanced, late-diagnosed, irreversible morphological changes do not leave such a chance, but today the presence of a coral stone inside the kidney, even a fairly large one, is by no means an absolute indication for removal of the entire organ. With the development of medical science and practice, the effectiveness of treatment for coral nephrolithiasis continues to increase while the invasiveness of the intervention decreases.

Further actions

Coral kidney stones are prevented by active disease prevention under the supervision of a urologist. A urologist, conducting dynamic observations, will be able to identify a dangerous tendency to the appearance of stones, for example, detect signs of changes in urine pH, hyperoxaluria, hyperkalyshemia, etc. and prescribe a course of corrective infusion therapy.

It is also advisable for the patient to follow simple rules: consume less table salt and fat, give up coffee, chocolate, sweets, fried and spicy foods. You need to drink a lot of fluids, at least two liters per day.